Wednesday marked the beginning of my journey west towards Western Australia and, ultimately, the state capital Perth, on the other side of the Nullarbor Desert. I spent the day driving the 415km to Wudinna, a convenient stop at the north of the Eyre Peninsula, where I met some guys from England who had just arrived from Perth. I got some handy driving tips off them, which helped me feel a bit more confident about driving such huge distances through the outback.

But the most memorable thing about Wudinna was my cooking. I'd stocked up on provisions at Port Augusta, a rather forgettable industrial port, and one of the things I bought was a 500g box of minced kangaroo meat. Supper for my last night in civilisation was therefore fettuccine with kangaroo bolognese, which was gorgeous; it was like traditional bolognese, but with a more tangy and meaty taste. It's hard to describe the taste of kangaroo, but if you ever get the chance to try it, do; it set me up for the longest drive of my trip so far... the trek across the Nullarbor Desert.

No Trees

Someone comes up to you in the street and says, 'Desert.' What's the first thing that comes into your head? 'Sand' maybe. Or perhaps 'very hot'. How about 'dry'? Or 'yellow'? Maybe even 'lemon meringue pie', if you're hard of hearing.

But the Nullarbor Desert, which fills an awful of a lot of central southern Australia, is none of these things, especially lemon meringue pie. It's a totally flat, vegetated area, although it's more scrubland than anything else; the name is a corruption of the Latin for 'no trees', which isn't quite accurate, it's just that the trees are either stunted to the size of bushes, or so straggly it's hard to believe they're alive. There are resident kangaroos, camels, snakes and all the other strange animals that inhabit this side of the globe, and being a desert, it's normally very dry... but not when I decided to cross it. Oh no.

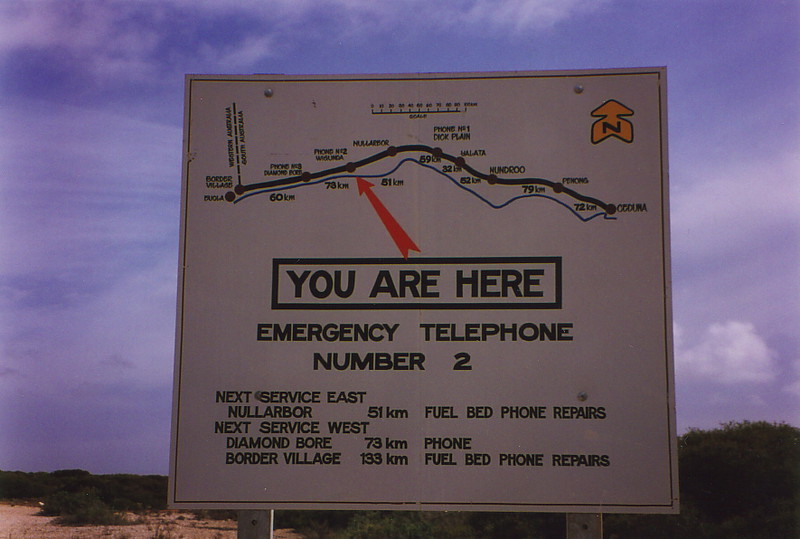

The real trip west across the Nullarbor begins at Ceduna, a sorry little place 770km from Adelaide that exists to provide a last town before the end of the world. The only settlements between Ceduna and Norseman, some 1200km to the west (and itself 720km east of Perth), are roadhouses and Aboriginal settlements, neither of which are terribly inviting.

The road is, well, pretty straight. The landscape, while different at one end to the other, looks the same as you drive along; it's flat and covered with little bushes and struggling gum trees. The only variation – and, believe me, any variation is a good thing – is the number of trees. Don't take your kids on this trip unless you've got Valium for the whole family; they'll drive you insane. Luckily I enjoyed it and discovered a number of interesting things along the way, but then I do have a good stereo and in the desert nobody can hear you sing.

I did the trip in two stages, the first from Wudinna to Ceduna and on to the Nullarbor Roadhouse (538km), and the second from the Nullarbor to Norseman (912km). I camped at the roadhouse, which happened to coincide with a desert downpour, forcing me under cover to cook my kangaroo burgers (just mix kangaroo mince with corn flour and some herbs, and fry 'em: very tasty). This soon forced me to concede that the best way to spend the evening was in the bar, making the inside of my head as soggy as the back shelf of my car. It was a good job I did spend the evening in the bar; when the wind blows in the desert, it doesn't blow, it howls. That's just one of the strange things about the outback.

Aboriginal Land

One aspect of Australia that is more apparent in the desert is Aboriginal land. There are a number of large areas of Australia that have been given back to the Aboriginal people – mostly unproductive desert areas, it has to be said – because they have managed to prove that they were there first (this is intriguing: the guidebooks always go on about how Aborigines lived everywhere, but of course they never get given the good parts, like the cities or the bits of land sitting on large mineral deposits). A number of important sites, like Uluru and Kakadu, are now Aboriginal lands, but are leased back to the government for use as National Parks; however, most areas aren't leased, and you can't go into them without a permit. One such place, Yalata, is crossed by the Eyre Highway (the road across the Nullarbor) though as long as you stick to the highway, you don't need a permit.

That's why there was a notice in the roadhouse bar, which said that if you were travelling in the direction of Yalata or Maralinga Tjarutja, another Aboriginal area to the north of the highway, you couldn't buy beer to take away, only low alcohol beer. The reason for this highlights a cultural situation in Australia. Because Aboriginal people never made wine or brewed beer, their first experience with alcohol was when the white man arrived, and as a result their metabolism never grew accustomed to it: Aboriginal biology has no tolerance of alcohol. The unfortunate side effect is that it takes very little to get an Aborigine off his or her trolley, so alcoholism is a serious problem among Aborigine communities, which is often quoted by white Australians as a reason not to trust the Aborigines.

The communities on reclaimed Aboriginal land, like Yalata, therefore ban alcohol from the area, as the whole point of the community is to live as they used to, living in harmony with the land, and not spending their lives lying in the gutter... hence the sign in the bar.

Sights of the Nullarbor

There are lots of strange things about crossing the desert, and one of the most obvious is the road train. Imagine a large lorry, and add another similar-sized lorry onto the back, and you've got a road train. They go ridiculously fast, and I got three cracks in my (new) windscreen courtesy of road trains coming the other way and stirring up stones from the side of the road. They're quite a sight.

Another sight is the coastline for the 100km before you reach the Western Australia/South Australia border. There are plenty of lookouts along the way, and the cliffs have to be seen to be believed. The Nullarbor plain used to be at the bottom of the sea (which is one reason for its sandy soils and lack of vegetation), but over time it rose straight up above sea level, and you can see the evidence in the cliffs; they're huge, white and totally vertical, for as far as the eye can see (except, of course, when the weather is miserable, as it was for me). The sea pounds away with no remorse, and the Eyre Highway passes within a few hundred metres for quite a long stretch.

The first lookout isn't a lookout as such; it's a gravel road that takes you 10km to the Head of the Bight, the most northerly point of the Great Australian Bight. It's not long before the Nullarbor Roadhouse, and I saw the sign and thought 'what the hell' and went for it. It was only after an age of driving along this awful unsealed road that I realised that if I broke down, or had a puncture, nobody would be along to help for ages, if at all. That's one reason why I carry 30 litres of water, 20 litres of spare petrol and a week's worth of food in the car; it's the recommended minimum if you're planning to visit the outback. Luckily I didn't have a breakdown, and the Head of the Bight was quite a sight, but I was glad to get back to the safety of the main highway.

As you head west after the Nullarbor Roadhouse, the cliffs kick in, and you can go right to the edge and peer over, if you don't get vertigo. Possibly the spookiest part is looking at the cliffs along the coast from you, and seeing how the edges look really unstable, as if they could fall in at any time. After a while of going west the cliffs gradually turn into flatter scrubland, with these incredibly huge sand dunes lining rough beaches; if it didn't look so dangerous, these beaches would be paradise.

Every now and then I'd drive over what looked like pedestrian crossings – in the middle of the desert! – which came in pairs, a kilometre or so apart, with a sign saying 'RFDS Emergency Airstrip'. It took me ages to work out that RFDS stands for Royal Flying Doctor Service, and they use the highway to land in emergencies.

Eventually you reach the border, 185km past the Nullarbor Roadhouse, where the lookouts stop and the drive gets long and pretty boring. It wouldn't be so bad if there were a bit of variety or something on the radio, but there's neither, and there's nothing to stop for on the way. Norseman, the first real town in Western Australia, is like an oasis; I stopped the night and had a long, hot shower for the first time since Wudinna.

'Sounds a bit unhygienic' you're thinking, and you're right, but water is really scarce in the desert. At the Nullarbor Roadhouse there aren't any taps, the showers are A$1 for five minutes of hot water – so I had a cold shower, and because it's so hot in the desert, it was actually rather pleasant – and the only water you can buy is bottled. It was a good job I'd packed plenty of water; there are signs in all the garages that tell you there's no water available, due to serious shortages; this is a desert, after all.

Desert Rules

Because it's a wilderness, the Nullarbor has its own rules. The most obvious one to a driver is the Waving Rule, another nicety of Aussie culture that I think I got the hang of, but I'm not sure. The idea is that, because the desert is so empty, you wave at oncoming traffic to say hello. That's easy enough, surely. Then why did only half of those to whom I waved wave back? Did they spot my Victoria number plates and think, 'Bloody Victorians, I hate them' and ignore me, or was it more sinister? And why, whenever I decided that enough was enough and I wasn't going to wave to these ungrateful buggers who didn't reciprocate, did someone then wave at me? The solution: just wave at everyone but don't look at them, so it doesn't matter if they wave back; you're being polite, end of story. The only problem is that when you're back in civilisation, you have this urge to wave at every living thing, and that doesn't really work when you're driving through a busy town centre.

You might also be thinking that 912km is a pretty hefty drive; at an average of 100km/h it's nine hours of driving, and that's no joke. However, I crossed three time zones during the journey, so by the time I got to Norseman I'd put the clocks back by two-and-a-half hours, making it just about the right length for a day's drive. There's logic in there somewhere... but whatever, by the time I'd reached Norseman, had the local police check the car to make sure I wasn't carrying any fresh fruit, vegetables or wool, I realised I'd arrived in Western Australia, and pitched for the night. At last I can genuinely say, 'G'day from WA!'