I don't know why I love camel trekking; it's the most uncomfortable experience this side of Mali's buses, but I thrive on camel treks. Naturally, the first thing Brook and I did on arriving in Timbuktu was to talk to the Tuareg camel trekkers outside our hotel about exploring the Sahara, and we soon settled on a three-night, four-day excursion to the surrounding area. I just can't seem to say no to camels and deserts.

I've done two camel treks before – one in the Thar Desert in India and the other in Merzouga in Morocco with Peta – and each time it's been an exercise in pain. Camels aren't comfortable creatures to ride and the fierce heat of the desert is no joke, but there's something endlessly appealing about lolloping through the desert on the back of such ponderous beasts, and even the sorest arse is a small price to pay for such a delightful experience.

I think it's the desert itself that really appeals to me; camels are just the best way to get around them. Deserts are so utterly hostile they're beautiful, and they command complete respect. You would die pretty quickly if you got caught in the middle of the desert with no water and no shade, and the very fact that you're surviving is half the appeal. Of course it's hot, and of course it's uncomfortable, but that's the whole point.

The Sahara of Timbuktu

Timbuktu isn't really in the Sahara, it's in the northern edge of the Sahel, the area of scrubland south of the desert itself. There's a lot of sand around Timbuktu but it doesn't drift into the endless rolling dunes one normally associates with the desert; instead it's dotted with squat trees, olive-green bushes and hardy little plants that look too dry to be alive but which seem to grow quite happily in the sand. More than anything the country around Timbuktu looks like the kind of dune system you'd find behind a beach; it's sandy, but it's also covered in vegetation. I half expected to see the glint of the ocean over the next gentle slope; the sea may be a very, very long way away, but Timbuktu still feels like a run-down seaside town.

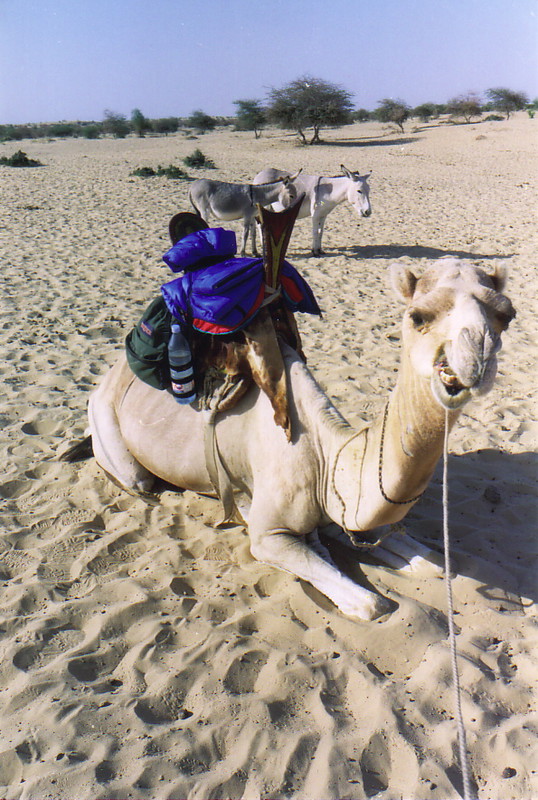

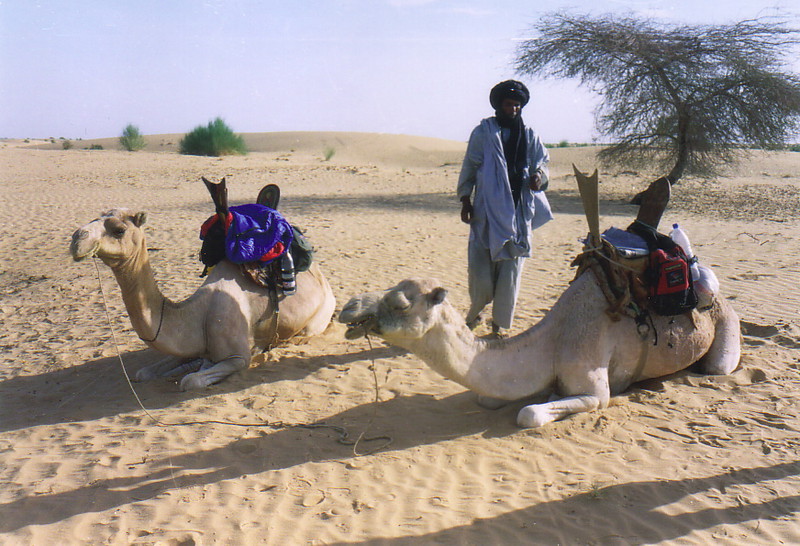

We met up with our guide, Ibrahim, on Monday afternoon, and as the sun sloped towards the horizon and the heat started to dissipate, he introduced us to our camel man, Barraka, and our two camels, Abza and Owrah, who smelled like wet blazers and burped and belched their way through mouthful after mouthful of regurgitated cud. I hopped onto Owrah, with Brook taking Abza, and before you could say 'Giddy up!' we headed out west and into the desert. From that moment I've been in heaven.

As I've said, camels aren't the most comfortable creatures to ride, partly because their legs fold up in such bizarre ways. Each leg has two knees, making them walk like a combination of a horse and a Swiss army knife, and the consequent rocking back and forth is a great way to wear out your inner thighs. But it's precisely this rocking motion that gives camel trekking its unique appeal, as you find yourself entering a strange meditative state that's not unlike the hiker's high you get when you walk for miles and miles without a break. Camels walk slowly, no quicker than humans at a sedate pace, and when you combine this rocking motion with the deadening effect of the sand sucking up all the sound around you, you get a truly relaxing calm. After the hustle of West Africa, it's especially beautiful.

As is the desert, even if it isn't made up of classic dunes. On the surface the desert looks practically lifeless, with the few hardy trees you see looking like casualties of a particularly harsh blight, but after a while you spot signs of life. People wander through the desert, their heads hidden beneath their turbans and the bodies smothered in flowing robes, and you soon realise that these guys live here; the distinctive domes of nomadic tents dot the horizon, big enough to house entire families and designed to keep the desert at bay; herds of goats and donkeys wander through the dry scrub, nibbling on anything edible while young boys herd them with little more than sharp sticks; strange piles of green balloons turn out to be watermelons, which the Tuareg farm on the outskirts of town; hobbled camels, their front legs tied together, stand motionless beside bushes, surveying the view; big bugs fly past with a noisy clatter, and black scarab beetles wander among the dunes, sniffing out dung for their supper; and all around on the sandy slopes of the desert floor you can see the footprints of birds, bugs and rodents, signs of life in an apparently dead environment. The Sahara, for all its harshness, is surprisingly full of life.

Base Camp

From Timbuktu we rode out into the desert and stopped at Ibrahim's house, where we've set up camp. Ibrahim, his wife, his daughter and his three sons live on a square patch of desert that they've cleared of scrub and surrounded with a makeshift fence of dry, dead wood, made up of thick branches of spiky, thorny desert bush. In the middle of the patch lies the family's tent, a traditional Tuareg tent that's the same colour and shape as an immense turtle, with patterned mats blocking up the sides below the roof; apart from a separate hut for cooking, that's their home. For our three nights out in the desert Brook and I are living on a large plastic mat draped in one corner of the compound, and that's it; we're camping under the stars, for our sins.

I love it. It gets fiercely cold at night and it takes a while to get used to sleeping on the sand – sand is, after all, just rock in a different form, and it's always harder than I imagine it will be – but there's almost a full moon that lights up the desert so we can see for miles, and the deadening silence of the sand makes it a wonderfully peaceful place to rest. We've been returning to Ibrahim's home every night for a meal of rice with bits of goat, and we're drinking water from the nearby hand-pump, miles away from the hustle and bustle of the outside world. (This is more than Ibrahim does, during daylight anyway. The Tuareg are a fiercely Islamic people, which means they respect the laws of Ramadan to the letter. Ibrahim eats and drinks nothing during daylight hours, even out here in the desert, and when we walked here on our first day, he was so weak he had to lie down for a while. I can't imagine what it must be like to voluntarily avoid drinking water in the desert; I drank gallons of the stuff, and still the dry desert air made my throat feel like sandpaper. The Tuareg are most definitely a hardcore people.)

Each of our two full days in the desert has followed the same format. I wake up with the sun at about 6am, lie staring at the sky for a while, and finally roll out of bed, stiff but alive. Barraka brings over a breakfast of coffee and bread with apricot jam, and I wake Brook – a much sounder sleeper than me – before ploughing through breakfast and downing half a bottle of water. We then saddle up the camels, fill up our 20-litre jerry can with water from the pump, and ride for a couple of hours until about 11 o'clock, when we pick a good tree to shelter under. Barraka then makes traditional Tuareg tea – strong Chinese green tea with lots of sugar, brewed up in a small metal teapot on a wood fire and served in tiny glasses – and cooks up a lunch of spaghetti or rice in tomato sauce with bits of mutton, and we sit under the tree until four o'clock in the afternoon, when we saddle up and ride back to camp. It's a simple little routine, and it's just what I need; I've been spending the middle of the day sitting, writing, thinking and drinking copious amounts of water and tea.

The ambling trek to and from camp has turned out to be a perfect way to relax. My mind wanders, sometimes happily, sometimes morosely, but the important thing is the serenity of it all. The desert is, above everything else, peaceful, and I've found it a haven after the hectic pace of the last six weeks. For the first time I feel myself relaxing into the experience, and I look around at the khaki sand dunes, the olive scrubland and the light blue sky, and realise, as I always do, how much I love deserts. Perhaps this was why I decided to come to Africa; if so, it's a bloody good reason.

What a shame it has to end tomorrow. One day, maybe, I'll do a huge camel trek across a real desert, where the dunes reach to the horizon and beyond. That would really be something; the Timbuktu desert is beautiful, but I'm sure the classic Saharan experience, for which you need to trek for days on end, would be something else entirely. For the time being, though, the Timbuktu desert is exactly what the doctor ordered. It hasn't quite managed to shake me out of my miserable mindset – the desert is not only a great place to pontificate, it's a great place to brood and wallow – but it has given me something to remember. I feel I now have the first real memory of my trip, and for this small mercy I'm grateful.