Yogyakarta is a famous tourist centre for a number of reasons, but the most impressive – after batik, for which the city is very well known, but which has been exported enough not to be uniquely Yogyakartan any more – are the temples and buildings in the surrounding area. I spent a whole day exploring the Sultan's Palace, watching some Javanese dancing and examining the batik shops, but this was just a stepping-stone on the way to the two serious sights of the area: Borobudur and Prambanan.

I tackled both temple complexes with the help of Tim and Bjorn, a couple of Belgian reprobates1 whom I'd met at the hotel, and who had been just as keen to sample the delights of Pizza Hut and McDonald's as I was. Swiftly proving themselves to be good company, we combined lazing around and cultural tourism in a way that only those with plenty of time and nothing better to do can. The fact that I was to spend a good ten days in Yogya waiting for a package that had never been sent2 was frustrating, but the Belgian boys made it more than enjoyable.

Cycling in Yogyakarta

The other 'cultural' event that we managed to experience in Yogyakarta – putting aside our junk-food visits – was a bicycle trip round the local villages and farms. For a tourist tour it was pretty damn good; Tim, Bjorn, myself, and our local guide headed off on the most astoundingly painful bicycles for a bone-rattling and arse-bruising trip into the paddy fields, and I have to say I learned a lot. Try the following, none of which I knew before cycling round Yogya. I mean, I didn't even know how rice grew until I took this tour...

-

Yes, rice. If you'd asked me before Yogya to tell you all I knew about rice, I would have told you it grows in waterlogged paddy fields, and, err, that's about it. But does the rice grow in the water or above water level? Does it grow in sheaths, like corncobs, or like wheat, or what? Well, here's the complete guide to growing rice.

Rice has a three-month growing cycle. Seeds are sown in a soft field by the traditional sower's-parable method, where they are left for 25 days to form baby shoots. These shoots are then transplanted into a new paddy field, where they are spaced out with 20cm between each shoot, measured using a bamboo stick with notches cut into it.

The field is left for three months. Fertiliser is added in the first month, when the water level is kept high, and the field is allowed to dry up during the second and third months.

By the end of the third month the rice has grown to about three or four feet high, and the seeds are in clusters at the end of the shoots, exactly like wheat or barley.

Workers threshing the rice by bashing bundles of it against wooden planks The rice is then cut down, and the seeds are removed by one of two methods: they are either bashed against wooden planks by energetic young men (the method we witnessed and, indeed, tried for ourselves), or they are stamped on. Whatever the method, the result is bags and bags of light brown seeds, the kernels of which are the traditional grains of rice; at this stage some are put aside to sow into empty fields, starting the process all over again.

The rest of the grains are laid out in the sun to dry for three or more days, depending on the weather; there are concrete slabs all over Indonesia, covered in yellow grains drying in the hot sun. Once dried, the chaff is separated from the kernel by throwing the grain up in the air from a round, flat bowl; the wind blows away the chaff, leaving rice. They sometimes stamp on the dried grains instead to separate the rice out, but it's a more common sight to see women tossing the grains like tropical versions of the American gold panners.

And that is where we get rice from. Thank you Yogya, for teaching me something that I really should have known in the first place...

-

The Pancasila. Ah yes, the Pancasila. On a large sign in every village in Indonesia are the five points of the Pancasila, a kind of creed for the Indonesian Republic, that was first put forward by President Soekarno in 1945, when he fought the Dutch for an end to colonialism. The five points each have a symbol, and they go together with the garuda to make up the main coat of arms of the Pancasila. Believe in it...

-

Star: This represents faith in one god. This god can be anyone – Christ, Buddha, Siva, Allah, whoever – as long as it's not subversive. People like the Torajans, with their animist views, have special permission to worship their idols.

-

Chain: The chain ring symbolises humanity, a sign that Indonesia is part of the unity of humankind.

-

Banyan Tree: This represents a united Indonesia, a coming together of all ethnic and religious groups into one united country. Incidentally, it's also the tree under which Buddha achieved enlightenment, but I don't think that's relevant to its inclusion in the Pancasila, seeing as Soekarno was a Muslim.

-

The Ramayana being performed in Yogya; on the left is the evil Ravana, on the right his sidekick Buffalo Head: The symbol for democracy, or at least Indonesia's interpretation of it. It's a democracy based on village deliberation, a governing of local issues by locals while the government makes all the important, nationwide decisions. Most Indonesians describe their country as a democracy, but this is a semantic subtlety; the government throws elections every few years, but seeing as the ruling Golkar party has the power to choose the opposition party's policies, leaders and election candidates, the balance is a little one-sided. Combined with Golkar's control of the media and its huge election resources, it comes as no surprise that President Soeharto tends to get around 70 per cent of the vote every time an election is called, as he has done since he turfed out Soekarno in the 1965 coup. This isn't a democracy that we would recognise in the West, though things do seem to be changing, albeit slowly.

-

Rice and Cotton Stalks: These represent social justice, or that a just society will provide adequate food and clothing for all its people. That presumably doesn't include all the beggars in the trains...

-

-

The Siskamling is a good example of the people's part of this democracy in action. In every village, at midnight, ten locals meet in a building called the Poskamling according to a rota, and tour the village, checking for any law-breakers, like thieves or murderers. If they find anything they call the police, but it's a clever way of taking the onus off the police to be everywhere all the time, and makes the people think they're responsible for upholding the law; Siskamling means System (sistem) Security (keamanan) Environment (lingkungan). Of course, the people are powerless over the government's human rights and environmental policies, but nobody seems to complain that much, as presumably the Siskamling would have something to say about that...

-

Brick making is a manual process in Indonesia; of course it is, as labour is cheap. Bricks are made from a mixture of clay and water, stuffed into a simple five-brick mould, and turned out onto concrete to dry in the sun for a week. That's all there is to it, and a good brick maker makes 500 bricks a day, worth 50rp each. Even breeze blocks are made this way: manually.

-

Tempe is a local delicacy, made by boiling soya beans for three hours, stamping on them, leaving them overnight, boiling for another three hours, mixing them with yeast and packing them in banana leaves. After exactly three days – no more, no less – the tempe is ready to eat, lightly fried in oil with garlic and salt. It's actually rather pleasant, but don't risk eating out-of-date tempe: it goes mouldy like there's no tomorrow, which will almost certainly be the case if you eat it.

It wasn't a bad haul for a day's cycling. We also invaded a school and thrilled a classroom of children with our strange ways – which wasn't scheduled: Tim and Bjorn just rode into the school and wandered into a classroom – and we saw peanut farms, corn fields, sugar cane, soya bean plants, teak trees, banana trees... and plenty of other weird and wonderful parts of the Indonesian countryside that you wouldn't spot from a speeding bus.

It was almost worth the sore buttocks, which hurt even more than after the buses in Flores and Sulawesi. Which is saying something.

Fort Vredeburg

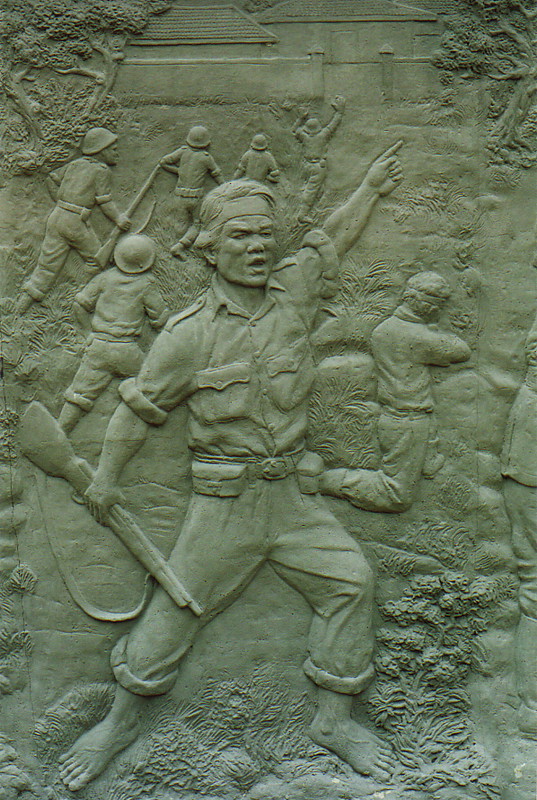

The other venue of note in Yogyakarta is Fort Vredeburg in the middle of town. This Dutch colonial fort is pleasant enough for its classic architecture, but more interesting are the three rooms of dioramas depicting the history of the independence movement (a diorama, I discovered, is the name given to a model of an event in time, such as the signing of an important document, or the invasion of a building).

The dioramas are interesting more for what they don't say than what they do. As should be expected from a dictatorship, the version of the story told in the Vredeburg is, well, rather biased. The first room tells of the early history of Indonesia, from the underhand Dutch capture of the local sultan and his exile to Sulawesi, to the creation of the health service and education system, right up to the beginning of the war. The second room shows the brutality of the Japanese invasion and occupation, and the end of the war. Both these rooms are captioned in both Indonesian and English, and both are reasonably fair.

But the third room is only captioned in Indonesian, and depicts the struggle for independence against the scurrilous Dutchmen and their underhand collaborators. Every Dutch soldier is depicted as mad with blood lust, and every Indonesian as heroic, of course. But I couldn't help wondering why the captions were solely in a language that most foreigners wouldn't understand...

1 Our relationship is probably best summed up by the fact that Tim and Bjorn said they'd buy me two large beers each if I shaved off my beard, so I did. Fickle, vacuous and college-boy stoopid it might have been, but I thoroughly enjoyed getting heartily drunk on my last night in Bali, at someone else's expense. It seems that if I run out of money, I can always count on my facial hair to bail me out...

2 My computer had died, and Acorn were kindly sending me a replacement, but it turned out that they couldn't send it to the Post Restante in Yogyakarta as the parcel company refused to send it to anywhere that didn't have a phone number. I would have to wait until Singapore to receive the replacement, which was hard to handle for such a technology addict.