A lot of people come to Jaisalmer for the amazing fortress, and plenty of them come for the wonderful desert atmosphere, but it feels as if the majority of tourists come for the camel safaris on offer.

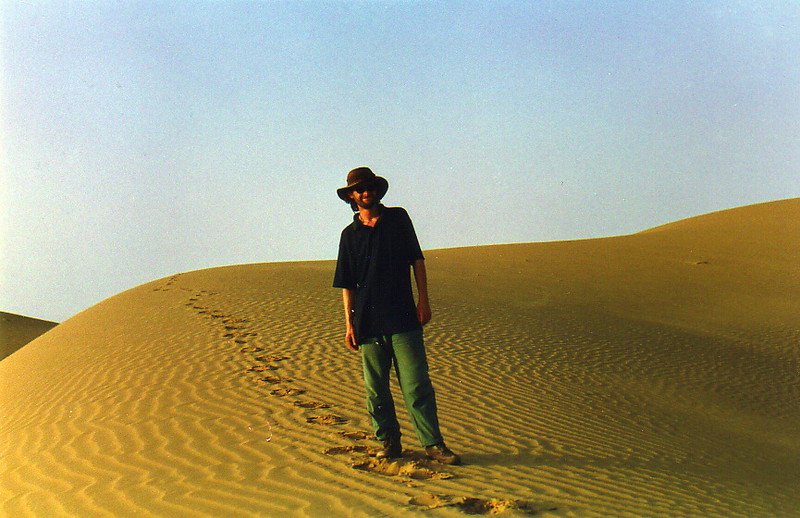

I was no exception, but visiting during the off-season proved to be a blessing. I'd met a friendly girl called Veronique on the Jodhpur train, and we were both interested in going on a safari, so we booked and waited to see if any more tourists would turn up. They didn't, and as a result we had a much more personal experience than we would have had in the busy season; with just the two of us, plus two guides and three camels, it felt like a real adventure as we headed off into the stifling heat of the Thar Desert.

Of the three camels, I was on Sukia, a true ship of the desert who came complete with a branded ship's anchor on his rear flank, Veronique was on Lula, and our guides, Ali and Sagra, variously rode and pulled Gula. Ali, an only child of Muslim parents (a rarity in this country of multiple-child families) was an interesting character; very clued up and with good English, he was an excellent liaison between the older desert expert Sagra and us complete novices. He sang Urdu trail songs, showed us his tiny home village, and always looked spotless in his white shirt and lungi. Sagra, on the other hand, was a Rajasthani Hindu through and through, with his twirled moustache, bright yellow turban1, holey shirt and well-loved dhoti. He spoke little English (most of his conversations were in the local language) and although he was a quiet man, when he spoke everyone fell silent and listened to what he had to say. The chemistry between the two was magical: the young business expert and the old man of the desert.

Veronique was no stranger to the desert either. She and her husband (who gave up his job as a journalist to study the subject of wine for a year, and is now export manager for one of New Zealand's top wineries) had toured southern Africa together, and she'd been on other trips there too, so luckily I wasn't in the presence of a dweeby indoors person. Not surprisingly, we clicked well. This was a good thing; life in the desert is hard. Your drinking water is always hot (which I found reminding me of good times in Australia); you sleep in the afternoon when the only thing that moves is the heat haze; the food is basic – chapatis and vegetable curry – but Sagra and Ali managed to create such variety out of so few ingredients that it was more than passable; pans are cleaned with sand and fires are made from sticks and cow pats; and you sleep on the sand dunes, a romantic idea but not quite the picnic one would expect. I thoroughly loved it.

Desert Life

As far as deserts go, the Thar is somewhere between the Sahara and the bush. There are dunes, but they don't stretch all the way to the horizon; you can see bush beyond the dunes, but they're large enough to get a feel for the desert. Out trip was for three days and two nights, both of which we spent sleeping under the stars, but I found I wanted to go for longer. Just like in Australia, the call of the desert is still strong.

There are enough differences between the Thar and other deserts I have visited to make it a new experience. The landscape is dry and rugged, but there is a fair amount of greenery; it isn't spinifex, but more like small, dry bushes. Trees dot the horizon, but not just any trees; these are mushroom-shaped neem trees, with the greenery stopping in a completely horizontal line some ten feet from the ground. I wondered how the science of genetics could explain that until I saw a camel munching at the green leaves; in the world of nature there's normally a good explanation for what at first appears to be an inexplicable wonder.

Unlike in Australia, where most of the life lives under the canopy (and is therefore very small), there is plenty of life in the Thar. I saw cows, camels, gazelles, goats, dogs, crows, beetles, lizards, desert foxes and, of course, humans, but it's still hard to see how anything can survive here in this arid land. I asked Ali if it rained much in the monsoon, to which he replied with a wry smile, 'It is the monsoon.' This doesn't stop the locals from ploughing fields ready for planting wheat, millet and camel grass, though I still fail to see how anything can grow out here; the lone woman and her child chopping at clumps of grass with a hook-back spade makes for a poignant symbol of man versus the environment. This is where India meets Africa and the frontiers of the old Wild West.

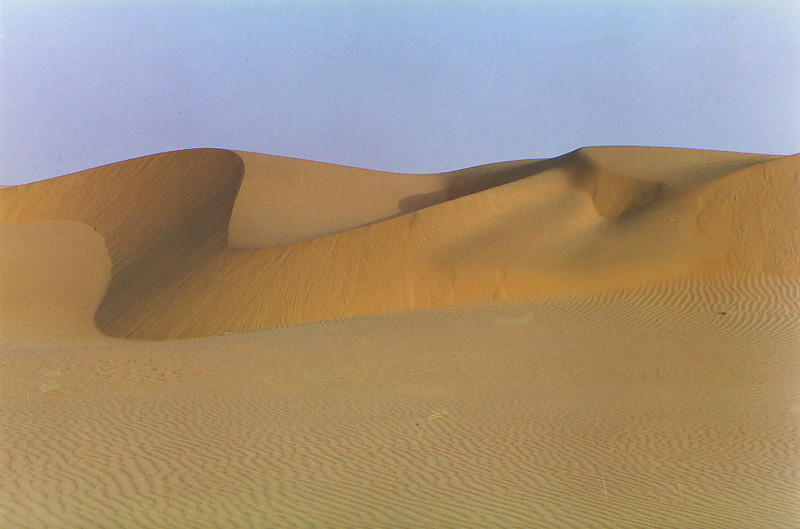

The Dunes

Perhaps the most romantic and evocative aspect of the desert is the amazing sight of the dunes. We spent two nights sleeping on their gentle slopes, an experience that is unforgettable not just for the thrill of the outdoors, but because it is far from the idyllic image it suggests. If the wind is blowing you wake up with sand in your mouth, sand in your eyes, sand in your nose, sand in your ears, sand in your hair, sand in your toes, sand in your crotch, sand in your armpits, sand in your fingernails and, after you've eaten, sand in your stomach. And sand isn't the soft surface you'd expect from all that sunbathing down on the beach; sand is just hard rock in little bits, and after a few hours of tossing and turning on a dune, you find that it's just as comfortable. But the stars are unforgettable – as are the satellites; for the first time I saw two in the sky at one time – and drifting off to sleep under the whole universe is a sight to behold. One night I woke up to see the silhouette of my camel against the starry horizon, and I couldn't help but start; this was a scene straight out of the books of Joan Aiken (and specifically the illustrations of Jan Pienkowski), a classic silhouetted scene of the type I grew up with in my imagination, and here it was, in the flesh. After an experience like that, it's a wonderful feeling to wake up to a cup of sweet chai and a pale blue sky, with Mercury rising as the mercury rises.

The dunes aren't just dead piles of sand, either; they're alive. When the morning breeze skirts the gentle slopes of the dunes, they shimmer with waves that make Hollywood's special effects pale in comparison. It is as if the dunes are pulsating with a kind of life, much as the plains do later when the heat stirs up the air to make trees, scrub and horizon waver in the haze. The whole dune system is made up of shifting sands, an impermanent collection of tiny particles piling up, collapsing and slowly eking across the desert in the direction of the prevailing winds, and it is in this sense that the dunes are truly alive. Like the camel trains and animal herds, the dunes are desert travellers, just in a different time scale.

More than once I was reminded of Thorung La, the snow fields on top of the world. There the wind blows streams of frozen water off the peaks and into the deep blue sky, and drifts of snow pile up over ragged mountain summits in a constantly changing landscape. And like the snow of Thorung La, the sand of the Thar Desert sucks in all sound, muffling footsteps and creating a silence that is beyond a pure absence of noise; you can hear your own body pumping, wheezing and gurgling, while all around the world is in golden silence.

It might be silent when the sun is baking the land, but there's always plenty going on. You won't see much wildlife in the severe heat of the midday scorch, but just look down and you'll see the evidence of the desert's huge variety of inhabitants.

There is the Pac-Man trail of the camel, a collection of croquette-shaped green turds in its wake; winding in and out of the dune bushes are squiggly lines made by the tail of a lizard scampering over the hot sand; hopping from foot to foot between the squiggles are the forked footprints of a desert crow; back on the path are hoof marks and the characteristic pat of a cow; scampering in the opposite direction are the cloven prints of a herd of goats, littering the ground in their wake with their bubble dung; following behind are the characteristic marks of two bare-footed humans, the prints deep into the sand from the weight of the water jugs balanced on their heads; and finally there is a slight movement among all the faeces as a dung beetle rolls a camel turd over and over, literally heading towards some secret shit-hole.

Desert Villages

More obvious signs of life dominate the far horizon: villages, dotted throughout the area, are easy to spot in this flat landscape. In this part of India, some 60km from the Pakistan border, the villages are mainly mixed caste, with all the Hindu castes living together with Muslims in one place. In the middle of the desert the people are simply stunned to see you; one day I skipped the midday nap and followed Noel Coward's advice, wandering off into the barren wasteland for an after-lunch stroll. As I emerged out of the heat haze like Clint Eastwood in High Plains Drifter and entered a lonely four-house village in the middle of nowhere, people came out of their front doors and stared as if I was a visitor from another planet, which in a sense I was; the desert is like nowhere else on earth, an inhospitable land made bearable by the construction of mud huts and wells. Some villages have water fed to them by pipelines, some have dug very deep wells to the waterline, and some even have the water flown in by aeroplane, but whatever the source, it's the water that provides a grip on the environment.

The buildings change as you get closer to civilisation, as does the attitude of the inhabitants. As we clomped slowly in the direction of the main road, the children became more tourist-aware, asking for pens and chocolate instead of just standing open-mouthed, and the mud huts morphed into ugly breeze-block monstrosities. Although the mud hut is much cooler than a stifling brick house, the brick house has a higher cost and therefore a higher status, so if you can afford it, you go for bricks. This attitude isn't confined to the desert; in Europe, we look upon stately homes as the ultimate luxury accommodation, but in reality they are difficult to heat in the winter, a nightmare to clean and a pain to maintain. But stately homes have a high status, and most people living in council houses would dearly love to upgrade; it's the same for mud-hut dwellers when they see the blocky designs of modern brick houses, even if they look to a westerner like ghetto material. Desert building work is an on-going process and is as insane as elsewhere in India; even out here the schools have walls round their grounds, though logically that seems like a waste of manpower and materials.

Towards the main road, modern life impinges. We were approached more than once by a man selling what he referred to as cold drinks, but which were, in fact, warm bottles of Pepsi, Teem and Mirinda. Pepsi has a firm grip on rural areas and Coca-Cola dominates in the cities, and it's nowhere more obvious than in the desert, where buildings display large painted Pepsi logos on their walls, clashing with the pastel colours of the surrounding desert. But that doesn't mean the people are modern; they marvelled at my penknife (which was much better than Sagra's blunt effort), inflatable pillow, eye shades, compass, collapsible cutlery set, bottle holder, sunglasses and even my cheap Indonesian sandals. But just as I thought I'd discovered one part of India where the West has no influence, the clock struck twelve and a chorus of digital watches bleeped to announce the turning of the hour.

Even out here, this is still India, with all its trappings.

1 A turban is just a piece of thin material, about 1m wide and around 5m long. As Public Enemy will tell you, it's all in the wrapping.