I forget how long I've assumed that Marrakech represents the sleaziest, most hard-nosed end of travelling. The first time I remember reading about it was in a book by James Michener, The Drifters, in which Marrakech was portrayed as a drug-addled place in which to lose your mind among the exotic souqs and smells of the medina. Then a friend I travelled with in Asia mentioned he had travelled in Morocco, and sucked in his cheeks as he complained about the amount of hassle he'd been given practically every single day of his visit. Marrakech sounded like India, but worse.

The truth is somewhat more mundane, possibly because things have changed a lot since the days of Michener and the hippy trail, but also because Marrakech seems to have cottoned on to the fact that hassling the shit out of potential clients is not good business sense (which is more than can be said for the rest of southern Morocco). Marrakech is a clean and orderly city that reeks of the exotic, but doesn't come close to India for hassle... or, indeed, trippiness.

Thank goodness for this, for the lingua franca of Morocco isn't English, it's French. The thought of trying to persuade a particularly insistent scam merchant that you don't want to buy a carpet off him is fine when he's at least speaking some of your native language, but when he's jabbering on in Arabic or French, you can't help but wonder if you've accidentally agreed to buy three chickens, a Berber rug and an ornamental perfume jar with detachable lid. In India I'd try quoting Beatles lyrics to those who would insist on chanting indecipherable sales mantras at me, but when you can half-understand what's going on, but only in a schoolboy manner, it's disconcerting. Thankfully the Marrakchis are really rather jolly and friendly, quite unlike the hassling image they seem to have.

It's possible that the way you are treated has a lot to do with the way you present yourself. Every guidebook you read goes on about the importance of dressing appropriately, and who can blame them. In a country where T-shirts are considered underwear and bare legs and tightly clad bottoms have the sexual electricity of women's breasts, the usual Brit-abroad vibe of shorts, flip-flops and pale flesh is the equivalent of wandering down the high street in a bikini, but this doesn't stop some people. I can only assume that it's these cultural ambassadors who attract the majority of Marrakech's hassle factor, because for those of us wearing trousers, shirts and an affable smile, the locals are a delight.

I was slightly disappointed, though. There's nothing like a calamity of humanity to wake you up after a flight, especially one that arrives in the middle of nowhere in the middle of the night, and Marrakech was almost too easy.

Exploring the Souqs

There are two things about Marrakech that the guidebooks can't stop raving about: the souqs and the Djemaa el-Fna. The souqs are a good way to get out of the sun, and the Djemaa el-Fna comes into its own at night, so we spent the best part of our first full day in Morocco wandering around the former.

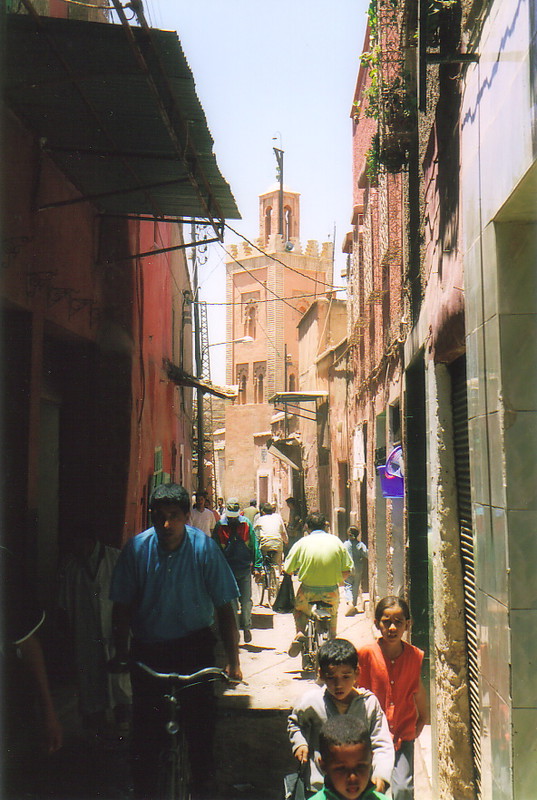

A souq is an undercover market, a mishmash of alleyways and shops that spill so many wares out into the narrow street that it looks like the inside of Ali Baba's tumble dryer after a sandstorm. The souqs in Marrakech are excellent examples of their kind, and they wind on forever... or they do if you get lost, and getting lost is all part of the plan.

If, like me, you couldn't give a toss about shopping but are more interested in immersing yourself in the cultural experience of Marrakech's souqs, then don't kick off your exploration halfway through the England-Argentina game. World Cup fever stretches all around the world – indeed, we saw plenty of football matches in the desert, let alone a cosmopolitan centre like Marrakech – and Morocco is close enough to Europe to be footy mad. Even working in a souq, where the hassle factor is legendary and the haggling practically physical, means nothing when the football is on, and coming out of every little shop was the roar of the televised crowd. Even the carpet sellers ignored us as we wandered through this Mecca of salesmen, their beady eyes glued to the ball instead.

It made navigating the maze of shops pretty simple, despite the fact that the souqs are completely covered, only letting the odd ray of sunlight penetrate the murky haze of incense and genie lamps. Normally, one assumes, getting from one end of Marrakech's souqs to the other would require a deftness of foot that even Ronaldo would find difficult, but remove the obstacles of leaping salesmen and lingering crowds and it's a piece of cake (one can only assume the other shoppers were watching at home, as the crowds were staying away in their droves). We shot through the souqs like a curling right-footer, and before you knew it we were blinking in the sunlight, wondering where it had all gone.

So we did it all again, this time from east to west, and yet again the only crowds and touts were on the TVs cunningly hidden beneath the curly toed slippers and woven hats. I'd expected exhilarating chaos and a severe test of nerves, and I found a pleasant shopping centre with lots of colourful goods and nothing to point towards the eccentricity of Africa apart from the lingering smell of drains. It felt a little, well, clinical.

One area managed to hint at the madness I'd hoped for. A small road branched left off the main drag, and pouring from it was a stench so nauseating it could mean only one thing: animals. And here we saw Morocco at its essence: men hoicked bundles of live chickens onto carts, the chickens tied by their feet into squawking clumps of ten, and sheep sat in their own stench in tiny cages the size of Japanese hotel rooms. Eggs were piled up to the ceiling and the stink was incredible, and everywhere we looked live animals were being treated as if they were dead. Unpleasant though it was to someone who's used to having his animal cruelty hidden behind closed doors, it was reality, and it breathed.

The football-crazy souqs, bless 'em, just couldn't compete.

The Djemaa el-Fna

The Djemaa el-Fna is famous as the cultural centre of Marrakech, and for good reason. Forming both the geographical and social centre of town, this irregular and open-plan plaza is part market, part restaurant, part theatre and part hippy festival. It's fascinating, and really comes into its own at night, for every evening huge crowds of locals and tourists pour into the square in search of entertainment, nourishment and, for some, increasingly clever ways of extracting money from visitors.

The souqs form the northern border of the Djemaa el-Fna, and in exploring them Peta and I had wandered through the heat-crazed midday square many times. While the sun beats down the Djemaa el-Fna is relatively quiet, the sounds of the cracking tarmac only broken by the cries of the 30-odd orange juice stalls selling freshly squeezed juice for a paltry Dr2.50 a glass. It's an interesting sight in its own right; Moroccans, as in most developing countries, tend to lump all their businesses together by what they sell, so you have the street where all the shoe polishers tout for trade, the jewellers souq, the carpenters souq, the former slave sellers souq, and so on. To a westerner, who is more used to having his shops dotted around town respectfully separate from each other, it's bizarre, and it makes you wonder how it is that so many outwardly identical businesses manage to survive. No doubt the Moroccans think we're insane doing it our way, too.

Besides, doing things our way would be unlikely to produce something quite like the Djemaa el-Fna at night. As the sun turns towards the horizon, rows of tables start to appear in the square, each surrounded by benches and shouting, touting chefs. It's not long before the smoke from countless barbecues fills the square with an eerie haze, as gaslights illuminate the clouds as they drift over towards the 70m-high Koutoubia Mosque to the southwest. It looks like a well-organised battlefield, and sounds like one.

'Bonjour monsieur, madame, you like brochettes, we have excellent saucissons, try our salade, you sit down here, best in the whole square, you remember, number 25 is the best, you come back later, we see you soon! Ah, madame, you looking hungry, you like chicken barbecue, best in square, ah yes, you sit here sir, welcome, bienvenue, bienvenue.'

We started our culinary introduction to Morocco with some snails from snail stall number one (one of five identical snail stalls all in a row), which at Dr10 a pop consisted of a hefty bowl of small snails in a soup that tasted like dishwater. The snails also tasted like dishwater, which one assumes is what snails taste like before you smother them in garlic and herbs, but most intriguingly they actually looked like snails.

Whenever I've had snails in a French restaurant they've looked like fairly amorphous blobs inside beautiful shells – indeed, the shells are re-used like crockery, and aren't the same shells that the snails lived and died in – but in the Djemaa el-Fna the snails look like snails. They're attached to their shells by all manner of intestinal goo, which you can only break with some deft work with a stout cocktail stick, and when you've pulled out the body and it's sitting there staring at you, you realise that it really is staring: the only difference between a live snail and your meal is that your meal can't move its two protruding stalks, but in every other aspect you're definitely eating a snail, with all of the intestinal excitement that entails.

The main course, though, is more conventional (unless you go for the stalls that sell whole sheep's heads, which do exactly what it says on the tin). We opted for number 25, simply because the chefs seemed to be having more fun that their neighbours, and Dr150 later we were struggling through mounds of gorgeous food, from sausages to kebabs to salad. The atmosphere, though, was the most important bit, especially when the wind changed and our meal disappeared in the barbecue smoke, an atmosphere made more surreal by the arrival of the local henna woman.

'Hello madame, I bring you good luck,' announced the woman from behind her litham veil, blatantly lying despite the evidence. 'I make Berber henna tattoo for you to bring you happiness with your children.'

'No thanks,' said Peta. 'That's very kind of you, but I don't want a henna tattoo.'

'But it bring you very good luck,' the henna woman continued, exercising the selective deafness that typifies the expert salesperson. 'Here, I do a small design for you to bring you good fortune and many babies.'

And with that she flipped out her henna syringe and started doodling on the back of Peta's hand, despite the fact that Peta was still eating.

'Bring you wonderful luck from God,' she warbled on. 'Ancient Berber design, beautiful colour,' she continued, despite the fact that it looked as if she was squirting goat shit onto Peta's hand. 'Small design, give you luck.'

By the time she had filled the whole of Peta's hand with green goo, and had started on the wrist, it was pretty obvious that Peta was getting a henna tattoo whether she liked it or not, and that we were going to have to pay for it. We bartered the price down from her initial fantasy price of Dr300 to a more affordable Dr70, but whether that represents a rip-off or not I have no idea... but I have a sneaking suspicion that whatever we paid would have been high. The moral of the story? If you want to say 'no', say it at least ten times, and mean it every time, otherwise you'll end up buying everything in the shop... and out of it.

But it's fun, just like the rest of the Djemaa el-Fna. As the day wears on, the rest of the square fills up with dancers, drummers and other bizarre stalls whose purpose is as mysterious as the pricing structure, and wandering around is a pleasant way to while away the hours and your small change (even simply watching requires a small payment, but at least it's not a tourist thing – everyone gets hit for donations, including the locals). It's surprisingly civilised, not unlike the souqs, and it didn't feel quite as anarchistic and on the edge as I'd hoped it would, but the ambience is unique and the evocative images delightful.

Just remember that the chances are you'll come away from the Djemaa el-Fna with more than you bargained for, even after bargaining.