-

Update Required To play the media you will need to either update your browser to a recent version or update your Flash plugin.

- Listen via a podcast [Help]

- Download as AAC or MP3 [Help]

Wrecker's yards, where cars go to die, are sad places. With twin headlights, a grinning radiator grille and a smiling curve to the bumper, your average car looks human, whether it's the frog-eyed bewilderment of the VW Beetle, the blockheaded bouncer look of the Volvo, the cute innocence of the Mini or the slit-eyed sophistication of the Ferrari. Stacks of rusting and half-dismantled cars look depressing because we personify them, subconsciously succumbing to images of retirement homes, mass graves and the inevitability of death. I should know; I spent plenty of time in Australia searching for bits to make my car, Oz, king of the road.

What about ships, though? With their proud bows and blunt sterns they're hard to associate with living creatures, let alone humans. Ships are sleek and ships are always female, but despite man's long history of glorifying and waxing lyrical about boats and the sea, from The Rime of the Ancient Mariner to The Old Man and the Sea, they're less human than vessel. The only personality I associated with Zeke – the yacht in which I sailed to French Polynesia – was that of gaoler, and despite the curves of the QE II and the gushing success of Titanic, ships aren't people, they're machines; that's why Herbie and Chitty-Chitty-Bang-Bang were cars, not boats.

But try telling that to someone who visits Alang. Stretching along the west coast of the Gulf of Camray some 50km southeast of Bhavnagar, Alang is the biggest ship-breaking yard in the world, and it has to be seen to be believed. Official statistics are hard to come by where Alang is concerned, not just because of the tendency of the locals to make things up, but because Alang has been the centre of human rights issues for some time and the government is more than a little sensitive about the whole thing.

However, gleaning what information I could from the local chai shop owners, I discovered the following. Alang consists of 400 breaker's yards (known as platforms) where somewhere between 20,000 and 40,000 workers dismantle ships by hand. An average ship has 300 people working on it at any one time, who take two months to break the ship down completely. The whole complex breaks about 1500 ships per year, and when I say 'ships' I mean everything from supertankers and war ships to car ferries and container ships. The statistics are impressive.

Getting to Alang

Because the working conditions are appalling and safety levels are laughably non-existent, Alang is a major draw for the poor of India who are desperate for a job, any job. People from Orissa and Bihar, two of the poorest states, make up a large percentage of the workers, but there are people from everywhere from Tamil Nadu to Nepal. I was waiting for the bus in Bhavnagar on the morning of Sunday 7th June – I took the phrase 'it's difficult to reach by bus, so take a taxi for the day' in my guidebook as a personal challenge, especially as there were four or five buses each way per day – and while I was trying to work out the bus timetable a sadhu wandered up to me, saffron clad and clutching a bag and a plastic container half full of what looked like month-old yoghurt. 'Where are you going?' he asked.

'Alang,' I replied. 'To see the ships.'

'So am I,' he said. 'I'm going to start work there.'

We chatted for a bit – his English was pretty good – and eventually the right bus pulled in and we hopped on. An hour and a half later we were sipping chai1 in Alang, looking out over the platforms where the ships lay in various stages of disarray.

The word 'platform' when applied to Alang is a euphemism; the platforms are simply beach. When a new ship is about to be broken up, the beach in the relevant yard is totally cleaned, even down to the last nut and bolt (nothing is wasted in this recycling operation), and then the ship is driven straight at the beach at breakneck speed so that it quite literally beaches itself. This part is finely tuned and has been done so many times that the ships are rarely more than a few metres off the desired position, which is a relief when you think of what would happen if they applied Indian bus logic to beaching a supertanker.

Alang is a suitable place for such crazy antics because it has a pretty eccentric tidal system. The tide is high only twice a month, which is when the sea covers the yards and new ships are beached; then for two weeks at a time the tide recedes, leaving the ships out of the water and easy to work on. And what work it is; everything that is detachable that can be sold is removed from the inside, all the engines are gutted and removed and then the ship's body itself is dismantled, chunk by chunk. The road into town is lined with large warehouses stacked high with doors, lathes, engine parts, beds, entire kitchen ranges, life jackets and plenty of other salvaged jetsam; you name it, if you can find it on a ship then you can buy it cheap in Alang. Most of the bits are trucked straight out to customers, but there's plenty left over for the high street stores.

The sight of a beached ship with half its front removed is both awesome and gruesome, because despite the lack of humanity in a fully intact ship, when it's sitting there with its guts hanging out it's hard not to pity the poor thing. It might be pity in the sense that we pity moth-eaten teddy bears or unlucky cartoon characters, but the sheer immensity of the beasts makes such pity harrowing.

I saw destroyers losing their final battle against the blow torch and hacksaw, I saw container ships sagging into the sand as the P&O signs were pulled down, I saw roll-on roll-off ferries rolling over and dying; even without an obvious face to each ship, it was slightly funereal.

But the appeal of Alang is also scientific. The whole place is like a huge, lifelike book of cross-section drawings, a real-life lesson in how the engines fit into a supertanker, how those millions of air vents and electricity conduits mesh together inside the hull of a navy ship, and how much of a ship is crammed with gear and how much is just empty space. In the West we are familiar with yards that make ships but not those that break them, and you don't make a ship from bow to stern, you make it in parts; the hull is built first, then the structural innards, and then the pleasantries of furnishing. In Alang it's a horizontal destruction irrespective of what order the insides were put in, and as such it's a unique sight.

Visit to the Ashram

I was impressed by the view from the chai shop, but what I really wanted to do was to get inside a yard and nose around; I wasn't stupid enough to want to climb around on a half-deconstructed ship, but some close-up views would have been great. My new-found friend said there would be plenty of time to worry about getting permission from the Port Officer later; first, it was time to visit his ashram.

This was an opportunity too good to miss. I've managed to avoid India's ashrams totally so far, and the thought of seeing one in such a godforsaken place as Alang was intriguing. We tootled along the road, past yard after yard and ship after ship, and soon ended up at the Siva ashram of the Gopnath Temple, a ramshackle but friendly complex surrounding yet another Hindu temple tucked away from the main coast road. Inside were other sadhus sitting cross-legged on some mats, and so we joined them.

I've often wondered what makes sadhus tick, and my visit to Gopnath confirmed my suspicions: they're a bunch of stoners. The man who was introduced to me as the big cheese at Gopnath ashram was puffing away on a chillum packed with charas (that's a pipe packed with marijuana), and as we rolled up he offered it to me.

I declined because it was obvious that Alang was going to be fascinating enough without chemical aid and I didn't want to get memory loss, but he packed another one and passed it round the circle, everybody inhaling right down to their toes except for me and a couple of guys who were having their palms read.

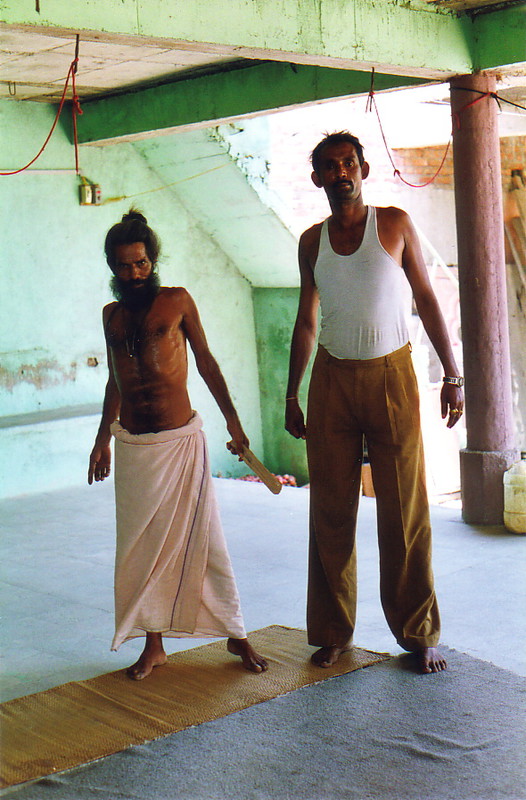

Five minutes later they were buggered but very hospitable, inviting me to dinner that night (which I also declined because I'd be back in Bhavnagar) and letting me take their pictures, as long as I promised to send them copies (which I did). But I wanted to see the ships, so I said goodbye to my now inert friend, who had decided to put off his job-hunting until four o'clock (though, come to think of it, he didn't say which day), and strolled back to the surf.

The Yards of Alang

I had previously met a few westerners who had visited Alang, and their advice had been not only to avoid taking pictures, but to leave my camera at home; unauthorised photography was not tolerated and would result in the removal of your film and undoubtedly a big baksheesh bill. I'd brought my camera anyway, and was mighty glad that I had; possibly the fact that it was Sunday made a difference, or the fact that it was high tide and the ships were being smacked by waves, but there were no workers to be seen, just a few lazing gate keepers, and quite a few of them let me in to wander among the guts of ships from all over the world. Only one of them asked for anything – two Cokes, which I didn't bother to buy him seeing as lots of other places weren't asking for a thing – and another bloke took a fancy to my biro (which he duly pinched) but there were no officials, no baksheesh issues and no problems with taking photos.

So I took 'em. The hotel man would later say that I had been very lucky being able to take photos – most tourists are apparently stopped and denied permission – and I would later meet a woman who had been accosted by a policeman with no badge, no gun and no proof of status except for his uniform (which looked suspiciously like a bus conductor's) who tried to charge her for her camera. I was lucky indeed; my experience was far from negative.

The yards were surprisingly clean; I had imagined oil slicks three feet deep and piles of rusting metal clogging up the environment. In reality the sea was fairly blue (inevitably it's not going to be mineral water round a ship breaking yard) and the beach was recognisable as sand, though I recalled that most of the objections to Alang from the international community were over working conditions rather than environmental concerns. Whatever the case, it's a good example of western hypocrisy because the ships keep coming, whatever the issues; dozens of ships were floating offshore, waiting their turn, looking well-used and battered in the way that only old ships can. For a fleeting moment I thought of homes for the elderly and waiting for God, but only for a moment. Ships aren't human, OK?

Cricket Among the Ships

The inhabitants of Alang are, though, and they're also incredibly friendly. As I wandered past the yards and admired the workers' slums leaning against each other, I smiled and got smiles back, I wobbled my head and got wobbling heads in return, and I waved and got raised palms for my trouble. And halfway back to the bus stand I came across a handful of boys playing cricket across the main road – steadfastly ignoring trucks and cycles as they turfed up the wicket – and they insisted that I join in.

I must have played for a good hour, batting and bowling my way into the history books. I was wearing my bush hat so I became 'Shane Warne' to the locals, and one of the boys who was a pretty good batsman became 'Sachin Tendulkar'. We drew a crowd and I drew on skills not used since school, but eventually it drew to an end, the heat killing my energy, ruining my spin and reminding me that I had to get back to Bhavnagar before I was stuck here forever. The people might be wonderful, but Alang isn't the sort of place you want to be stranded in.

Finally, my Bhavnagar hotel just served to underline how friendly the area is. The previous night I'd dropped my bag onto a marble table and the bloody thing had come loose from the wall, smashing on the ground and shattering; even the Rolling Stones would have been impressed by my ability to ruin a hotel room so comprehensively. I assumed the reaction would turn into a barely restrained discussion on how much I would have to pay, but what was the reaction in Bhavnagar? 'I am sorry, sir, would you like to have a different room?'

I was gobsmacked, and hardly wanted to leave.

1 This is a different act depending on where you are sipping it. Normally chai is served in a glass, either in a small full glass or a large half-full glass, in which case you just drink it normally. If you're served chai in a cup and shallow saucer, you should pour the chai into the saucer and drink the chai from the saucer. Finally (and this is more common in the south) if you are served chai in a cup and deep saucer, you should pour the chai into the saucer, then pour it back into the cup, and drink from the cup; this is to mix in the sugar that's sitting idly on the bottom, so if you don't like your chai sweet you don't pour it and mix it up. Oh, and 'service tea' is the name for the way we drink it in England, with separate milk and a teapot, but that's service tea, not chai. Chai is to tea what McDonald's is to haute cuisine... except chai tastes great!