During the early stages of the Circuit, I was less concerned with getting AMS and more worried about an old friend. On the fourth day into the trek I felt a familiar stirring in my stomach and soon had the eggy-belch blues, and I realised that the giardia I'd first picked up in Puri had come back. Again.

So I took an emergency rest day in the small village of Bagarchap and spent the morning feeling sorry for myself, before plucking up the energy to walk up to the village of Chame, where a rickety old hospital building perches on top of a steep hill. Presumably the journey is designed to put off all but the most determined of the sick, and after struggling up the hill and explaining my predicament to the resident doctor, I was given a week's course of metronidazole, making it three doses of strong drugs that I've tried on this persistent parasite; the other courses of secnidazole and metronidazole clearly didn't do the trick.

Luckily, this dose seemed to work; it certainly stopped the worst symptoms, but it had the added side effect of knocking me out. Metronidazole is firmly in the 'don't operate machinery' category, and as the week's course lasted until after the pass, I spent a lot of the ascent in a bit of a daze, and that was on top of the lightheaded feeling that you get at altitude.

We also lost Jakob to a mysterious stomach illness, and there were plenty of other stories of people getting ill on the trek. For some reason the Annapurna area is home to a bewildering array of nasty ailments, and this is another reason why I class the trek as difficult; walking with a dodgy stomach and AMS is a bit of a nightmare. And irrespective of whether you actually get trekker's stomach or AMS, the high altitude means you get out of breath after just a few steps and have to rest a ridiculous amount. It makes the hardcore trekkers quite depressed; hills they would normally conquer before breakfast take all morning to walk up, however strong they are at sea level. Man just wasn't meant to fly.

But the trek is well worth all this medical trauma. From the lush lakeside town of Pokhara you travel along valleys that become increasingly steep and desolate as the altitude lowers the temperature and the treeline approaches. Every day the huge peaks of the various ranges lean closer and closer, looming over tiny settlements where houses are cobbled together out of yak dung and shaky cement. It's an amazing part of the world.

On the Track

The sights along the way are uniquely Nepalese. Lines of grey donkeys wend their way along the thin footpaths, each decorated with garish bridles and low-toned bells, swiftly followed by wiry men wielding split sticks and yelling, 'Ho!' A little boy points cow eyes up at us as he points to his badly cut toe, which we dutifully clean and bandage, suggesting to him in English that he really should wear some shoes while it heals, a piece of medical advice that disappears into the language barrier.

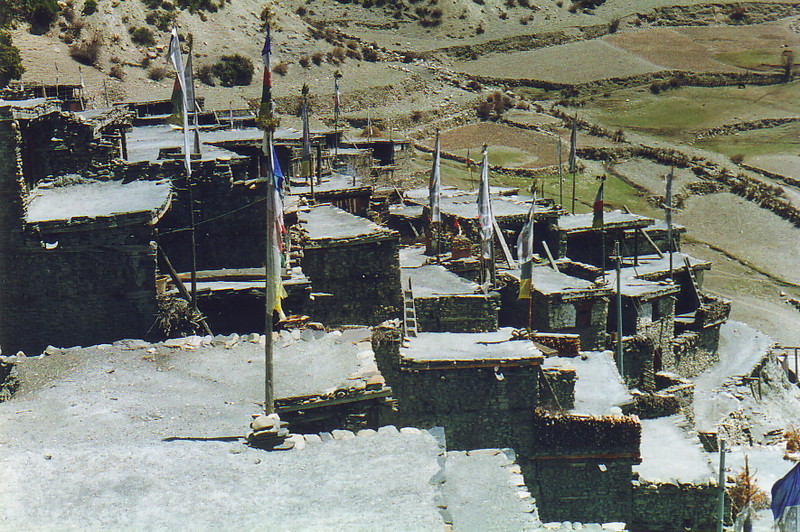

Further along the trail is the town of Bagarchap, where a landslide destroyed the town in , taking a number of trekkers and locals with it; there are numerous memorials dotted around the town, which I explored when taking an enforced break due to my giardia outbreak. Here the locals are still rebuilding what once must have been a beautifully picturesque little town, and I spent a recuperative afternoon riveted to the veranda table watching the women carry huge baskets of stones on their heads as the men broke up massive boulders into smaller, more manageable rocks for rebuilding their porches; throughout the whole job the workers smiled, laughed and joked in a way that's sadly absent from the western workplace.

And if you think that your backpack is a little too heavy as you scratch your way up yet another steep mountain path, Nepalese porters keep plying up and down the tracks, carrying incredibly heavy baskets on their backs, suspended only by a strap around the forehead, which means they support the whole weight with their neck muscles. I thought the porters in Indonesia were pretty impressive, but the Nepalese are even more iron willed. The amazing energy of the locals is most apparent in the hotels and footpaths that form the Annapurna Circuit. Gaping yawns in the mountains have been filled with row upon row of flat rocks to form pathways; sheer granite cliffs have been chipped away or blown up to give a clear passage; stone steps have been set into the mountain sides to ease the ascents and descents; and suspension bridges arc across steep-sided gorges from towers built from rock and cement. But the hotels are even more amazing, with their restaurants, dormitories and hot shower systems; although the food is pretty basic compared to places like Pokhara and Bangkok, it's a refreshing change to have to live on a potato and porridge diet after such a long love-hate relationship with rice and noodles.

Actually, the impressive thing about the food isn't so much the taste, it's the fact that so many ingredients have to be carried in. There are no roads around the area, and yet the hotels manage to feed up to 70 hungry mouths at a time, which might not make that potato soup the most thrilling culinary experience in the cosmos, but it does deserve a round of applause. I still fantasized about steak and beer and had to make do with a lot less, but it was a lot better than the awful crud I normally cook for myself on the trail.

Another interesting result of the porters carrying everything in is that prices go up as you get further away from Pokhara. That Mars bar you paid Rs40 for in Kathmandu is Rs80 just before the pass; a cup of hot lemon from the last tea house before the pass, shivering well above the snowline, will set you back a princely Rs40 compared to Rs5 down at more atmospheric restaurants; plain rice rockets from Rs10 to Rs50, because it's so heavy to carry; even Coke, the universal price index, leaps from Rs15 to Rs60, which sounds outrageous until you consider how far it's had to travel.

This price change seems to mirror the trip itself; the pass is such a momentous occasion that the Circuit naturally falls into the days before the pass, and the days after the pass. As you approach the pass the prices go up, the temperature goes down, the trees shrink and eventually disappear, the snow gets closer, the air gets thinner and the landscape gets bleaker and bleaker. By the time you reach the first acclimatisation town, Manang at 3535m (11597 ft), life is getting harder; mild AMS, which affects most people at this stage, creates an ache at the base of the neck, makes breathing more difficult and walking up the street a serious exercise, and the temperature at night means sleeping is that much more unpleasant.

I found that a major portion of my AMS paranoia was taken up with a serious increase in cynicism; I began to have a major problem with walkers who weren't in my small list of Excellent People (though, of course, I kept this to myself). The silly Canadian whose Calgary accent made my eyes roll to the ceiling and my air-starved lungs let out an exasperated sigh; the know-it-all Englishman who came up with useless idiocies such as, 'I've had giardia three times and all I do is miss a meal and it goes away,' and who earned the nickname Jesus from the other walkers, a sarcastic comment on his seeming omniscience; the Squeaky American who reminded me of that super-wet character in Police Academy; the girls from North Carolina who didn't know the rules of chess ('Tell me y'all, how many of these liddle pahwns do y'all start with, now?') and who had an incredible lack of knowledge when it came to accents of the rest of the world ('Are y'all Australian?' 'No, ve are from Germany'); the doped-out American college student who kept exclaiming how cool the Diamox hit was, buzzin' fingertips 'n' all, man; and the insane Rasputin clone from Switzerland with his zany sense of humour1. They made me think of a particularly far out episode of the Twilight Zone.

But there was one thing that bound all of us together, weirdoes and cynics alike, and that was the continuing group psychosis. As I've already mentioned, AMS is by far the most popular subject of conversation, but other obsessions crop up with increasing regularity: the height of the current town (in dispute because every map has a different figure on it); the times for walking a certain portion of the track (also at variance, depending on your source); the quality of the food; the pros and cons of Ibuprofen as an anti-inflammatory; the advantages of a genuine Gore-Tex jacket over a fake one from Kathmandu; the amazing price of a pot of coffee in that last village; the best way to treat blisters; and so on and so on. You can approach anyone on the Annapurna Circuit and enter into an instant conversation on aches, pains, drugs, food and gradients, but try to delve too deeply into politics or finances and you'll soon find yourself drifting back to the subjects of aches, pains, drugs, food and, let's not forget, gradients...

The local culture, tainted though it obviously is, changes markedly through the different regions too. From the touristy lower regions of the east side and the rugged wind-ravaged desolation of the northern reaches, to the holiday-home mentality of the Jomsom track on the west of the pass, it's possible to peer into a way of life that is as authentic as Schrödinger's cat; your very investigation changes things. The monasteries dotted around the valleys dispense Buddhist and Hindu blessings to walkers, be they Indian sadhus or Australian accountants, and although the gompas are undeniably authentic, their collections of dusty Dalai Lama pictures and meditating Buddha statues ensure a continuous tourist trade, fired up by the antics of Richard Gere and a continuing mysticism surrounding Tibet.

I was blessed in two gompas, once in Braga on the east side of the pass, and once in Muktinath just after the pass, and although it was a fascinating insight into the surreal nature of the eastern religions, I felt like I was encroaching on territory reserved for true believers. As the mumbling monk in Braga chanted mantras that sounded more like the contented sighs of an old man sitting by the fire, the prayer wheels whirled and the incense smouldered, but did the wisdom of Lord Buddha fill me with foreknowledge of the passage through the pass, for which I was receiving blessing? And did the whirling dances of the Hindu priest in Muktinath make the whole experience of puja any less theatrical? Of course not; I watched, I listened, I washed myself in the 108 taps round the temple (a guarantee that you will go to heaven, by the way), I received the forehead markings and I ate the crystalline sugar, and I left with pictures rather than puja. Even the eternal flame of Muktinath turns out to be a scientific event; natural gas escapes through a vent that's always lit, not so much a Light that Never Goes Out as a Gas Bill that Never Gets Charged.

Over the Top

For crossing the pass I teamed up with Bob and Sheldon; the Canadian girls had forged on a day ahead, but we wanted to take our time acclimatising and stayed longer at lower altitudes. Jakob had already fallen by the wayside, but apart from that we'd managed to make a good team, and as such we'd been bouncing the paranoia off each other like a prism magnifying sunlight. By the time the altitude reached the point of AMS, I was riding high on a wave of hypochondria.

We'd done our acclimatisation walks, where you walk 200m or so higher than the place where you will sleep, thus aiding the metabolic changes that need to take place in acclimatisation (such as lowering body acid levels, which means excessive urination as the acids are flushed out; an expansion of lung volume and a deepening of lung capacity; and a loss of appetite followed by slight nausea). But nothing prepared me for the sheer panic of altitude that made my last night on the east side a nightmare to remember.

It is simply freezing up there on the side of the pass. Sunlight helps, but as soon as the sun dips below the horizon the temperature shoots below freezing. Snowfall is not uncommon, and winds whistling through the cracks are a common feature. AMS, by this stage, has become a familiar friend, the slow pale throb of white noise at the back of your head, a migraine in the making, threatening to turn into something more serious at any time; appetite has all but disappeared, and every meal time is a struggle against instinct; simply walking up a short flight of stairs is an exercise in breathing steadily and resting frequently; and dehydration from the diuretic effect of acclimatisation takes its toll, especially late at night as the symptoms get worse. On my last night before the pass, up at around 4400m in Thorung Phedi, I slipped into sheer misery.

Tossing and turning, fully clothed and stuffed into my sleeping bag, I froze my way through a dreamscape of confused and contradictory images. In glorious Technicolor I dreamed I had severe AMS and had to be taken down to the next town on the back of a donkey while the headache split my skull and I was copiously sick, despite my low food intake. I woke up in the nearest approximation to a cold sweat that you can have in sub-zero temperatures, and spent the rest of the short night dreading the crossing and dreaming of home.

We set off at 5.40am, Sheldon, Bob and I shuffling slowly through the snow onto the roof of the world. We had all popped a Diamox pill, the recommended prophylactic and treatment for AMS, and I assume it helped; we all managed to get over the top without incident (if you ignore the severe shortages of breath, a nasty headache in my case and a general malaise caused by high altitude exertion) and although the views of the top of the range and the surrounding landscapes were unique and unlike anything I've ever experienced – the silence on a snow-smothered summit is eerie, to say the least – the effort was severe. Was it worth it?

Of course it was. I learned what it is like to exist in an environment that makes every rule of existence seem like a vindictive headmaster's revenge. Breathing is constantly laboured, mealtime becomes a psychological trauma, the head aches in cycles from dawn to dusk, sleep patterns are ravaged, toiletry functions become more insistently regular than after the five-beer mark, and conversation becomes truly one-track: it's all AMS, AMS, AMS. Then there are the ailments of snow blindness (you have to wear sunglasses constantly to avoid becoming blind, literally), windburn (lips and nose beware), sunburn (the sun is distressingly close up there), muscle strain (from carrying a pack up to 5416m) and trekker's knee (from the long, long descent). But nearly everyone makes it, and the sense of achievement is totally different from exploring rainforests or trudging deserts. When I finally collapsed in Muktinath on the west side of the path, I swore I'd never do anything like that again. I probably lied.

1 Two of whose jokes must be saved for posterity, because it's rare that I come across jokes so devoid of any humour that they couldn't even raise a smile on a terminally stoned sadhu. Try out the following corker:

One day I was sitting in a shopping centre, and a fly came buzzing up to me, so I caught this fly and put it into a paper bag that I had. Then I walked around the shopping centre and went to a supermarket, where I joined the queue. When I got to the till the lady asked me, 'What is this?'

'It's my fly,' I replied!

Seriously, you were supposed to laugh! How about this blockbuster, then:

When I was young the teacher asked the class, 'Now children, what do you want for Christmas?' When it came to my turn, I said, 'An elephant!'

The Taste Police have been informed.