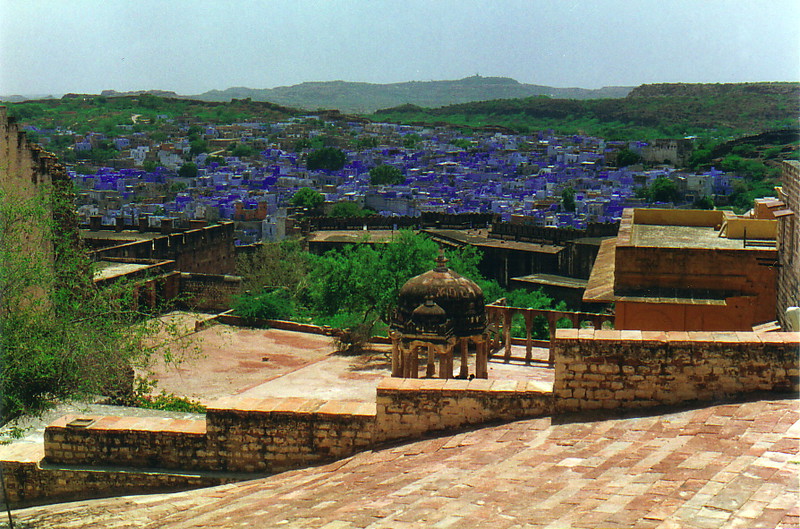

Jodhpur isn't only famous for its hard-nosed businessmen, it's also home to one of the most staggering fortresses you will ever see. The Mehrangarh Fort dominates the city, sitting atop a 125m-high cliff-edged hill that catches the rising sun beautifully.

Not only that, my hotel, a beautiful 250-year-old haveli right in the centre of the city, was a classic of its type. A haveli is a traditional Rajasthani or Gujarati building, consisting of a number of floors based round a central courtyard. Most havelis used to be mansions; these days they're more likely to be hotels, offices or home to many families, but a good haveli manages to retain its atmosphere and makes for an interesting place to stay, especially if you can get one of the lower rooms, tucked away from the searing sun.

After spending a couple of days being entertained by Yogi and Babaji, I finally found time on my last day to visit the fort, which was my main reason for visiting Jodhpur in the first place. I was by no means the first person to visit the place; in 1899 Rudyard Kipling wrote of the fort:

The work of angels, fairies and giants... built by Titans and coloured by the morning sun... he who walks through it loses sense of being among buildings. It is as though he walked through mountain gorges...

This might sound grandiose, but Kipling doesn't overstate the immensity of the place. Huge walls sheer straight up from the cliff edge, serrated battlements provide ample room for huge cannons and view-hungry tourists, and even though her eloquence was hardly that of Kipling's, Jackie Kennedy managed to sum up the fort with the wonderfully hyperbolic, 'The eighth wonder of the world!'

The Money Man

On my way through the winding streets leading up to the eighth wonder of the world, I met a man. As per usual we got talking, but it was obvious from the start that this man had done his homework even more thoroughly than most.

'What is your country?' he asked.

'England,' I replied.

'Ah, England. Prime Minister is Tony Blair.'

'That's right!'

'Before that, John Major.'

'Spot on.'

'Before, Margaret Thatcher. Then James Callaghan. Then...'

And on he went, reciting the last few Prime Ministers backwards as if he were a kid in a history lesson. I lost track at Thatcher; I was nine when she deposed whoever was before her, and I felt a little embarrassed to see that this guy knew more than me about British politics.

While we were talking, a little boy slid up and sat down. He looked at me and started a familiar conversation.

'What is your country?' he asked.

'England,' I replied.

'Ah, England. Prime Minister is Tony Blair.'

'Er, that's right,' I said, smelling a rat.

'Before that, John Major. Before, Margaret Thatcher. Then James Callaghan. Then...'

'OK, OK,' I conceded, beaten again. I looked at the man who was beaming with pride.

'My son,' he said, and ruffled his boy's hair affectionately.

'I have a collection of money notes,' said the boy, and when I launched into my well-rehearsed monologue of how I had no coins or notes from home because I had been away for so long, he broke in and said, 'Just come and take a look, I don't want to take any notes from you. Just come and look.' And charmed by his excellent English, I padded behind him into his home.

His mother made me chai and I looked at his note collection. It was huge; 'The biggest in Rajasthan,' my new friend Awatar announced. There were notes from Slovenia, Yugoslavia, China, Vietnam, Argentina, America, Canada, Italy, Sweden, Bangladesh, Nepal, Cambodia, Singapore and plenty of other exotic locations... it was fascinating.

I asked him where on earth he had got all these notes, and he said 'tourists' in such a plaintive way that I found myself promising to send him a note from England, seeing as he had nothing from the UK in his collection (I hope he received the mint £1 note I sent, itself an oddity1). He was so pleased that I had to catch myself as he moved into scam mode.

I mentioned I was going home in July, via Amsterdam, and his face lit up. 'Maybe you can help me,' he said. 'I have a friend whose mother is very ill in hospital, and needs money. He has some Dutch money, and maybe you can buy it off him for rupees.'

I asked him why he didn't just change it at the bank, and he said that only foreigners could do that, not Indians, but I wasn't into it at all. I didn't know the exchange rate and he was talking about quite a large amount, so I refused and instead found him proffering two pound coins.

'I got these from tourists,' he said, 'but I do not collect coins. You can use these at home; do you want to change these?'

This time I took the bait. The coins were genuine, I offered him Rs60 per coin (an offer slightly to my advantage) and he went for it. Emboldened by his success, he started jabbering away until we found ourselves on the subject of school, which was when he fished out a sealed clay pot with a coin-sized slit in it and gave me the usual blurb about collecting money to buy pens for the local school children, and would I like to donate? No, I said. He told me that Rs100 would buy five pens for the local school, which is an atrocious price for a pen (they're not that expensive in England) and I realised that if I didn't get out he would talk me out of all my worldly possessions and probably even more.

But what did I expect? This is Jodhpur, and the creed here is obviously salesmanship and money, as I've been discovering. Awatar's note collection was evidently genuine and worth supporting, but even he couldn't avoid the vocational calling of the genetic con artist, despite his tender age of nearly 15. It wasn't malicious, it wasn't even a con – everything he suggested was fair and above board, just pushy – but I was a guest in his house, drinking his chai, offering to send him something for his collection, and still he couldn't resist trying to pull a fast one on the tourist. This is the sort of thing that leaves a slightly bad taste in my mouth, and it seems Jodhpur has made subtle deception its tour de force.

The Fortress

I finally escaped to the fortress, where the man at the gate asked me where I was from, and when I told him he said, 'Ah, England. Prime Minister is Tony Blair.'

Wandering through the main gate, the guides waiting to be hired called me over, asked me where I was from and proclaimed, 'Ah, England. Capital is London, Prime Minister is Tony Blair.'

And when I waited to have my ticket ripped for entry into the museum, the turban-clad attendant asked me where I was from and politely told me that the Prime Minister of England was the one-and-only Mr Tony Blair.

I felt quite exhausted.

But the fortress is certainly impressive, and the museum is one of the better Maharaja's museums around (though it still pales when compared with evidence of George of Gwalior's kleptomania). There are beautiful palace buildings, shady courtyards, intricate stone lattice works, and trademark Rajasthani rooms filled with mirrors and coloured glass (which manage to retain an air of taste, unlike Udaipur's efforts). However, a lot of the fortress is closed to the public, so for my Rs50 entrance ticket and Rs50 camera permit I didn't really feel I got my money's worth.

It was still excellent to visit, but again I felt a little aggrieved at pouring money into the Maharaja's coffers when government-owned sites like Mandu and Bijapur charge fees between two and five rupees for unlimited access. Awatar's father had also expressed disgust; with Indians only having to pay a Rs10 entrance fee, he felt it was unfair on foreigners when for things like train journeys and hotels there is no distinction between Indian and foreigner. I have no problem with being charged more for being a foreigner – we have more money, after all – but I'm less happy when the only people doing this are the aristocratic owners of places like Mehrangarh Fort.

There is one feature of the fort that is definitely worth paying for, though. Standing on the battlements, the wind blows over the city and up the ramparts in such a way that you can hear all the noises of the city below you, as clearly as if you were standing in the streets yourself. Aldous Huxley, in one of his more lyrical moments, wrote:

...from the bastions of the Jodhpur Fort one hears as the gods must hear from Olympus, the gods to whom each separate word uttered in the innumerably peopled world below, comes up distinct and individual to be recorded in the books of omniscience.

That's as maybe, but what I heard from the battlements was a calamitous cacophony of chaos from crashing clutches to crowded chowks and clopping cows. I idly wondered if Huxley ever visited the Golcumbaz, as Forster did; now that is a real ear on infinity.

And it's a darn sight cheaper, too.

1 Many thanks to Matt Kilsby, who got in touch with the following message:

I'm currently travelling around India and have found your website really helpful and bloody funny as well!

I'm currently sitting in an Internet café in some backstreet in Jodhpur (it's all a bit of a maze, though). This morning a friend and I went up to the fort, and who should accost us on the street? 'Prime Minister Tony Blair... etc.' I knew what was coming next because I'd already read your section on Jodhpur. Lo and behold, out came the foreign note album and I must say that it's a fantastic collection! I was also offered a two pound coin. Six years later the cute teenager is now a fully fledged Indian businessman.

As to the note that you sent him... there were two one-quid notes in his collection, one from Jersey and the second a Royal Bank of Scotland one. If either of those notes are yours, then they are sitting proudly in his album (can't remember the page number unfortunately!).

Anyway, thanks again for this great site. Keep up the good work. I'm off to get lost in Jodhpur.

Thanks for letting me know, Matt. Unfortunately the note I sent to Awatar was from the Bank of England, so I suspect it got lost in the post. Ah well, someone somewhere is a pound richer...