In reading the story of Yogi and Babaji, bear in mind that throughout the experience I had a song going through my head, namely Sheryl Crow's ode to kiss-and-tell journalism, 'The Book'. Here's an excerpt:

Never again

Would I see your face.

You carry a pen and a paper

And no time

And no words you waste.

You're a voyeur,

The worst kind of thief,

To take what happened to us,

To write down everything that went on

Between you and me.

Is that me? Am I being a voyeur, stealing the (possibly) good intentions of two traders to provide me with an interesting story? I don't think I am, but judge for yourself. Personally, I don't think the following is so much 'kiss and tell' as 'get him pissed and sell'.

In my travels I've met plenty of locals whom I trusted implicitly. Pavan, the man I met on the train to Gwalior, is an example; we conversed on the train through politeness, he invited me out for a meal and insisted on paying, and I trusted him. I knew that his motives were pure in that he was interested in meeting me and I was interested in meeting him. Similarly I trusted Kiran, whom I met on the train from Puri to Hyderabad, because he was incredibly genuine and honest.

But my visit to Jodhpur made me reconsider this blind trust, not because I had a particularly negative experience, but because with some people – in all countries, not just in India – you should only trust them as far as you can spit. And not being a habitual pan chewer, for me this is not very far.

Yogi to the Rescue

Let me tell you a story. On my arrival in Jodhpur – the town that gives the trousers their name (though these days you'll see more jodhpurs in Gujarat than Rajasthan, as far as I can see) – I decided to book my onward train ticket straight away, to avoid having to rely on the local Louis to save the day again. Unfortunately the computers were down in the ticket office, so I joined the 'Tourists and Freedom Fighters' queue for what I assumed would be a long wait.

That's when Yogi introduced himself. Sporting a pockmarked face, a beer belly and a jaw line that can only be described as an investment paying dividends, he was instantly amiable in the same way as his cartoon namesake. He chatted away, leaving me to mutter the usual politely distant rubbish of 'Really, how interesting, I see, is that right?' while the computers continued to refuse to kick into gear. He told me he taught the sitar, which interested me, and I humoured him. He was pleasant enough, and claimed he didn't meet many tourists out here in Jodhpur so he was very pleased to talk to me (though I would later discover that in the high season the Mehrangarh Fort gets 400 foreign visitors every day, a pretty high figure).

After nearly an hour of standing around waiting for the technology to catch up with the demand, a not unusual situation in India, I was visibly tiring. The bus journey from Mt Abu hadn't been unpleasant, but seven hours on a bus is a long time whatever the road surface and Yogi could tell, so he offered to get my ticket for me. I would meet him later for a beer and some food, and I would pay him for the ticket then, and because the ticket has the price printed on it, and the price is directly related to the length of journey, it would be impossible for him to rip me off. Grudgingly I accepted; I like to do my own dirty work, but the prospect of waiting for someone to hack into a PC network while the workers all sat around on an extended chai break filled me with something short of enthusiasm, so I agreed. Yogi would come and pick me up that night, and we'd go to his brother's place for a feed and a couple of beers.

So far so good, and indeed Yogi turned up spot on time on his moped, complete with the promised ticket. We drove to his brother's place because it is not permitted to drink alcohol in a room devoted to teaching music (this I had heard before), and we ended up in a machine shop just round the corner from the railway station. In this shop was a ladder, and at the top of the ladder was a trap door, which Yogi unlocked and pushed back. And before you could say, 'Open sesame!' we were in Aladdin's cave.

The small attic was chocka-block with, well, things. Garish Rajasthani puppets hung in one corner; shelves of metal-cast models of Ganesh, Siva, Buddha and the rest of the boys filled another; a glass-topped counter containing jewellery ran along one side; and a sign proclaiming that they preferred Visa hung next to another that said, 'We know you are trustworthy but we are forgetful, so please pay in cash.' Every well-honed scam-detection circuit clicked into place and I turned to Yogi and said, 'You do know I'm not interested in buying anything, yes?'

'You are my friend,' he said. 'I already tell you my brother is in the export business, but we come here to drink some beer, have some food, not to sell. If you are interested, that is one thing, but there is no pressure. I promise you. You trust me?'

If there's one thing I do not trust it is people who ask me if I trust them (as in 'You trust me? I trust you...'); if there is one thing guaranteed to break a friendship, it is a constant querying of the status of the friendship (as in 'You are my friend, no?'); if there is one thing that makes me suspicious, it is someone who is paranoid (as in 'Why you ask all these questions? I tell you there is no pressure here.'); and if there is one thing that puts me on total alert, it is someone who takes me into their shop when a large part of our earlier conversation has been about how offensive I find the shop-touts in places like Jaipur and Agra. From the moment I entered the shop, I became a man alert to every scam in the book.

The problem is that after spending two days with Yogi and his brother Babaji, I still do not know if they were genuinely friendly or just out to get something from me. Because of this uncertainty I cannot say that I ever felt friendly with the two brothers in the way that I did with Pavan, but it is quite possible that they were indeed genuine and that all my doubts were the product of a cynical mind. So see what you think...

Evening Shenanigans

That night I sat with Yogi, Babaji and a friend of theirs called, somewhat interestingly, Bob, and I never let my guard down. In a pique of pleasantry I had bought a gift with me: my collection of ten cassettes had long lost its appeal and my Walkman had never really recovered from the bus ride to Diu, so I gave my tapes and stereo to Yogi. This sounds awfully generous, but I was about to ditch them on the next traveller I could find who wanted them, because they were bulky and low fidelity brings me down. It doesn't seem to affect the Indian aural sensibilities though (judging by the quality of, er, hi-fi here), and I figured that Yogi, as a music teacher, might appreciate the gift.

The cynic would say that this unexpected gift knocked the wind out of their prospects for selling me things; the empiricist would argue that there is no evidence for there being any kind of set-up and that my own paranoia had invented the whole thing. Whatever happened, the gift went down well. I felt contented and socially at ease as I supped on my beer.

We then came to the meal, of which we were to split the cost. No problem: with four of us, that makes it a quarter each. So how did I end up putting Rs400 into the pot and getting one beer (Rs70, fixed price) and a quarter of two dishes and a couple of nan breads, a meal I could buy in its entirety for less than Rs150? The food was good, the beer was certainly strong, but was I being ripped off? And how come only two of us, Babaji and me, were paying? This was no four-way split.

But I chipped in because they were being so pleasant, and because they assured me that the restaurant delivering the food was one of the best in Rajasthan (and just happened to be next door to the attic office). The cynic might say I was being easily milked for a few extra rupees – no, a lot of extra rupees – because they figured I might not know the real cost of food in India. The empiricist might say that the meal was indeed that price, and that being rich Brahmins (Babaji owned two cars, a house and a shop) they were used to spending large amounts of money on food, and assumed that as a westerner I would find it well within my budget.

I rolled with it. The beer was taking effect, the ambience was fascinating as my paranoia fought against my faith in the Indian people, and I didn't feel threatened at all. But things continued to get stranger and stranger, always suggesting a scam without necessarily coming to fruition. Was I being expertly worked and was simply proving too stubborn or too poor to con, or was it all a total figment of my imagination?

The next oddity happened when Babaji read my palm. Now, telling me my stars is about as pointless as telling a Christian to have a good time in the Coliseum; I don't believe in the signs of the Zodiac, and I only read the stars in the paper if I've run out of news to digest. But out of politeness I feigned interest and submitted to scrutiny.

I have to say he did a thorough job. Out came the magnifying glasses, the tables of squiggles and symbols, and the generalised predictions about my past that were either obviously culled from my earlier conversation with Yogi (I had told him I lived in Birmingham, for geographical simplicity, and Babaji pronounced that I lived in a place beginning with B, which is untrue both for London and the place I'm actually from), general enough to be true of anyone ('You are happy', he told me, which was pretty obvious to anyone meeting me at that point), simply wrong (Babaji told me that I trust what people say too much, and this while I was constantly thinking how little I trusted these two characters), or obviously just what I wanted to hear (he told me that in two and a half years I would go travelling for at least nine months, a safe prediction and obviously in tune with my thinking at the time, although this would also turn out not to be true). I was unconvinced, but in the spirit of forbearance that I learned on board Zeke, I made myself sound thrilled and interested. That was possibly a mistake.

My reading ended after I had discovered various uninspiring facts about myself; I was 'lucky', I would make a large sum of money in the very near future, I would not marry until 38 but would meet someone special soon... the usual stuff that's designed to please and is therefore easy to believe if you are willing enough. But there was more; my lucky stone tuned out to be a star ruby and apparently I should wear it in a silver pendant shaped like a crescent moon. I don't wear jewellery, but it just so happened that Babaji had one such pendant left, and perhaps I would like to see it.

I simply said that this was obviously a hard sell and I wasn't even interested, and that caused sulks the like of which I hadn't seen since my visits to primary schools in New Zealand. 'We are doing this for you, for your good luck,' they cried. 'You are friend, do you not trust us?' I said of course I did (lying my back teeth off) but that I wasn't going to buy jewellery. 'If you don't buy this stone,' said Babaji, 'it means you do not believe in anything I have told you.' And he let out an almighty sigh, one of resignation rather than of sorrow.

What do you do? I looked at the pendant, reiterated my stand on buying nothing, and left it at that. They shrugged, looked hurt and put the stone away. The cynic would say that this was an obvious scam, so obvious I should have been rolling around the floor in glee at having stumbled on such a rich source of stories. The empiricist would say that they genuinely believed in astrology, it being a fundamental part of Indian culture and a very serious part too, and that they were sincerely trying to help me with my luck. I simply didn't know which was true, but the decision was easy because they were talking around Rs500 for the pendant, a figure I would consider imprudent to invest in anything except a ticket out of Jodhpur or a very good book, neither of which were available in Babaji's shop.

You must understand that my scam-detection units were all aflutter by now, having detected a potential chink in the overt friendship exuding from the brothers. I tried not to get cynical, but whenever money was mentioned, I firmly said, 'No.' But the greatest scam of the lot cropped up not half an hour later, and I still don't know if I was being cast a line or given a real offer. The cynic would say this is the hallmark of the perfect con: the conned doesn't know he is being conned until far too late. The empiricist would say that business is business, and what Babaji told me made a kind of sense.

The Gem Scam

Some background information first. There is a classic scam operated by gem dealers, mainly in Agra and Jaipur, which makes use of the tourist's tax-free import allowance. Tourists from most western countries can import goods up to a certain value into their own country without paying import tax (currently the amount for the UK is US$5200); this is a fact, and it makes a lot of sense when you think of tourists buying gifts and souvenirs and bringing them home. The scam involves a gem dealer asking a tourist to import some stones for him, so the dealer saves paying the import tax, a portion of which goes to the tourist; all the gem dealer needs is a deposit from the tourist to cover the cost of the gems, and he will give an assurance that the tourist will be able to contact the dealer's partners in his home country, and they will buy the gems off him for much more than the deposit. So the tourist makes lots of money, and the dealer is happy because he makes a good sale.

Of course this is complete rubbish. The tourist effectively buys a bunch of worthless gems off the dealer, often paying amounts like US$2000 for them, and when he gets home he finds the contact details are a complete fiction and that his gems are worth a fraction of what he paid. It's a ridiculously obvious scam and one which even the lobotomised should have trouble getting sucked into, but on my trip I met at least two suckers who had fallen for it, and the stories abound of others stupid enough to give thousands of dollars in cash to complete strangers. Then again, these are the sort of travellers who think that karma is what you get after taking a sedative, and what can you do about that?

So when Babaji mentioned my import allowance and how I could help him import gems into England tax free, I couldn't help laughing; I now saw that the part in my horoscope about me receiving a large sum of money in the next few months was simply a lead-in to this whole tax allowance set-up. I said that this was the most famous scam of them all, and that there was no way I would ever get involved, no way at all. He said that he would actually be posting the gems to me, and that all I would have to pay would be the registered and insured postage, but I looked at him and told him that if he was a real businessman selling the stuff in England, he would pay for absolutely everything, including a cut for me. He told me I had to speculate to accumulate, and I told him to drop the subject and, no, I didn't trust him any more. How could I?

They were horrified, or good actors. They had never heard of such a terrible scam, they said. They were shocked to hear that I thought they were out to rip me off, they said. They promised to drop the subject, they said, and after bringing it up twice more in the evening, they eventually did. The cynic might say that they realised I was too clued up for their plan to work. The empiricist might say that they really wanted to avoid paying tax and saw a way I could help; after all, Babaji was supposed to be visiting England in a few weeks' time.

Whatever the reality, the evening ended with a ride back to my hotel (with them kindly paying for a rickshaw to take me the last part home). I had arranged to meet Yogi at the railway reservation office at noon, and after a leisurely hangover-cure breakfast, I did just that. I was intrigued by my total uncertainty about the brothers, and I figured that if I took almost no money and no passport I would be safe; I had left all my documents behind in the hotel room the night before as a precaution, and I decided to stick to this plan to avoid heavy losses if they drugged my drink or took me down a dark alley (unfortunate accidents that happen to plenty of tourists in the backstreets of this dog-eat-dog world).

The Sitar Scam

The original plan for the day had been to take the bikes out to a Rajasthani village to show me some real Indian life, but it was far too hot to hit the desert for an hour's drive, so instead Yogi and I settled in for a beer and a chat. I learned some interesting things, such as the fact that Yogi drank Rs200-worth of beer every day, which at least provided an explanation for his Ming-vase profile; but the most intriguing thing I learned was his total lack of understanding of my finances. He seemed genuinely surprised that I was not a rich tourist, and perhaps he realised I meant it when we got onto the subject of the sitar.

After receiving my gift the previous day, Yogi had insisted that he give me a present in exchange; I was flattered. He said he wanted to give me a sitar; I was overwhelmed. This was great! A sitar! One of the most insane instruments in the world, for me? As a gift? What a champion.

But the subject of money cropped up again, this time in the guise of postage. He wanted me to pay half the postage, which sounded fair until I found out that he wanted Rs1800 for my half, or about US$45. I detected another possible scam, and so I told him I was on a really tight budget, especially this near the end of my trip, and could never afford that much money. OK, he said, we could send it by cheap sea mail, but I would still have to pay US$20. I said I simply couldn't, and seeing an opportunity to make my feelings known, I charged in with horns down.

I told Yogi that I had paid a huge amount for the meal the night before and felt ripped off. I told him that if I had a guest in my house in England, I would not expect him or her to pay a cent, unless they felt obliged to buy a round of drinks or to bring a gift. I told him I would never continually bring up the subject of money and buying items from the shop; this I would class as unforgivably crass and rude. I told him that I was interested in astrology, but I didn't believe, so there was no point in buying a stone for something that I went along with for the fun of it, especially if a big guilt trip was laid on me.

Eventually we reached a compromise. He would pay the postage, and when Babaji came to England a month after I was back, I would meet him and buy him a bunch of beers. This suited me fine; there I'd be on my home turf, and by then I'd also know if the sitar had actually arrived, in which case it would be only fair to buy the man more beers than even he could quaff.

The subject of the village trip then cropped up, seeing as the day was wearing on and the temperature dropping. I was interested until I heard it would cost me something like Rs200 in petrol, a ludicrous figure given the village's proximity and the average cost of petrol; once again I felt I was being offered interesting options, but only if I was willing to pay through the nose. I decided against the trip, and instead settled for a second beer. But the prospect of another expensive evening meal loomed, and I had to do something if I wasn't going to be swallowed up by these financial vultures.

I said I couldn't afford another meal, and that I would eat elsewhere and meet them later for a beer. This caused the usual offended demeanour, downcast eyes and drooping jaw line, but Yogi suggested a solution; we would visit a friend of his who lived on a nearby farm (yes, a farm in the middle of a city) and eat there for nothing; all I would have to do would be to bring the family a gift of sweets, and maybe buy the man of the house a beer. This was fine by me; farmer's families are poor, and besides, it sounded culturally intriguing. I accepted gratefully.

Meanwhile Babaji had returned, and immediately launched into the sort of psychological warfare that makes talking with certain Indians bear a striking resemblance to walking on broken glass. He asked me questions like, 'Mark, what do you really think of me? Tell me the truth, now...' And I answered truthfully in much the same way as I had with Yogi. So answer me this: how in hell's name did I end up buying a tiger-eye stone from him for Rs151 (an auspicious number, I was told)? It was my lucky stone, to be worn next to my skin for good luck, and on reflection it was his apparently total conviction that this stone would be really good for me that made me fork out the money. You see many Indians with arm bands containing their lucky stones, so I suppose I thought what the hell, it's a cultural thing, but it's possible that I bought it partly as a token of my appreciation of his sales technique, and partly to shut him up. In the case of the latter it seemed to work, but the cynic would say I fell into the trap eventually, and that the sale had to happen sooner or later. The empiricist would say I didn't have to buy anything, and hey, it's a purchase with a story, isn't it?

Urma's Farm

That night Yogi, his farmer friend Urma and I hopped on the moped and span through the backstreets of early evening Jodhpur. This was fun; to give Yogi his dues he always drove slowly and carefully, an unusual trait in Asia, and we soon arrived at a sweet shop (where I bought a box of assorted sweets) and moved on to Urma's house.

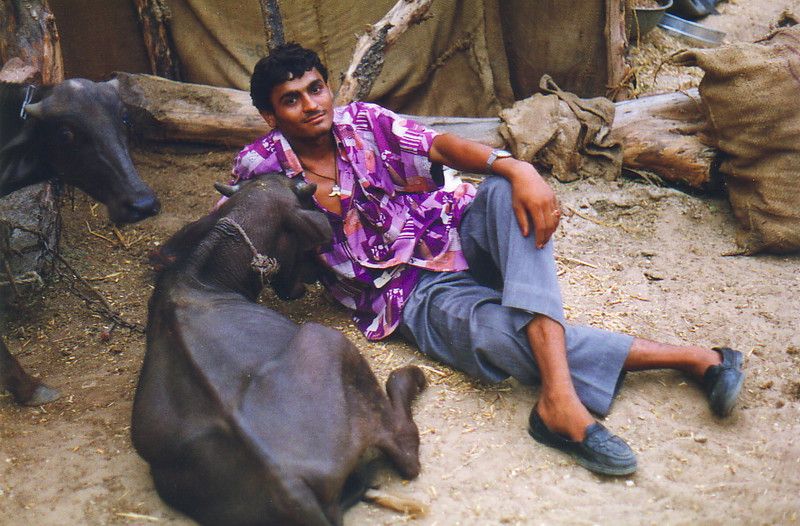

House is the wrong word. Imagine a small block of land, maybe 20m by 20m, stuck in the middle of a suburban sprawl. This block of land had no buildings on it save a small mud and brick hut in one corner, and tall walls of housing blocks loomed on three sides, the fourth being protected from the chaos of the street by a tall fence. Filling half of the block was a small herd of huge buffalo and a couple of cows, the buffalo attached by nose rings to stakes driven into the ground; along one side of the wall ran a roof covering large blocks of dried grass feed, one corner contained a huge pile of dried buffalo shit, patted together so that the handprints were still clearly visible, and another side held a roof under which some more buffalo sat, viewing the proceedings with a detachment only available to those who can fill their spare time by eating their last meal all over again.

It was, as promised, a milk farm in the middle of the city. Urma, his mother Rupei and his sister Nirma pottered around, wide-eyed and reduced to giggling fits by the presence of this white stranger, and when I fished out my camera and took a bunch of shots in the fading light, they posed with their buffalo like people who had never posed for a camera in their lives before (which quite possibly was the case). The instant I pointed the lens at them the smiles disappeared and they assumed the austere poses of Victorians, a sight I hadn't seen since the pictures of Gwalior George standing over dead tigers, and it made me wonder at this universal effect of photography; in the West we are so used to pictures that we tend to relax more in front of the lens, but here it's different. I promised to send them copies of the pictures, and made sure I did.

As the meal was being prepared – chapatis being fried in a pan over a roasting buffalo-dung fire – a goods truck pulled up and out poured a complete extended family: cousins, little children, uncles, the whole shooting match. Unintelligible conversation flew around me like smudges of mashed potato in a food fight, leaving me smiling in ignorance and wondering whether the discussion was about world politics, the state of the financial markets or the fact that the neighbour's son had run off with the niece of the cat's father's milkman's cow. I ate my plate of chapatis and fresh buffalo curd with ghee and glee, risked drinking the water (which would prove no problem) and thoroughly enjoyed the completely authentic atmosphere around me. Children marvelled at my funny language and funnier beard, old men tried their rusty English on me, and I sat on a charpoy staring at the scene as the sun disappeared and the night rolled in.

It was, as Yogi had said it would be, a cheap and thoroughly wonderful experience. We celebrated with a final beer back at the shop, but surprise, surprise, I ended up forking out to cover Yogi's lack of financial solvency, and ended the night back at my hotel with my host owing me the princely sum of Rs85. This was not a lot of money, but this whole financial imbalance thing was beginning to wear me down.

Chance Meeting

The final chapter in this saga came the next day, my last day in Jodhpur, after I had visited the Mehrangarh Fort. Wandering back through the streets round the railway station, I saw Babaji wandering along and he spotted me straight away; Australian bush hats aren't exactly common fare in India. We went through the usual social niceties, and then I asked him where he'd disappeared to last night. He said, 'Oh, I was too hot, so I went home. Fancy a cold drink?' Too right I did, so we ducked into a chai shop for a couple of bottles of Pepsi. It was good to chat, and amazingly enough Yogi chose that moment to wander into the same chai shop, just as Babaji was telling me that he was on the way to one of his factories to get a ring made for another customer who was paying Rs7000 for a star ruby set in a silver ring. This was very good business for him in the off-season, and I congratulated him on his luck.

So how the hell did I end up paying for all the drinks? Babaji said he had no change, only a Rs100 note, and before you know it I had shown him my hand and coughed up the dough. Why? This man was telling me all about his hot-shot business deals, and I was his guest, but I still paid. Am I that much of a pushover?

Finally, I arranged to meet both Yogi and Babaji at the railway station restaurant to say goodbye before I boarded my night train to Jaisalmer. I made sure I ate before I met them (to avoid any more financially draining food expenses) and turned up at the appointed time. Rather interestingly, for the first time they totally failed to turn up, leaving me sitting in the restaurant for a good two hours, free to enjoy peace of a sort. Babaji had said the lucky effect of my tiger-eye would be instant, but I didn't realise it would be fast enough to spare me the ordeal of entertaining the Dodgy Brothers before having to board my overnight train. It's marvellous stuff, this astrology, even if Yogi still owed me Rs85 at my time of departure, the shyster.

Incidentally, a couple of Australian guys I met in Udaipur and Diu told me that after hanging around with a group of locals for a few days, they'd needed an 'Indian-free week' to get over it. They were worn out by the constant social intrigues and petty offences they managed to cause, and decided to take a break. I didn't understand what they meant at the time because all my Indian liaisons up to that point had been simply delightful, but as I got on the Jaisalmer train, I felt rather relieved to be escaping and totally understood the Aussies' sentiments.

Needless to say neither Babaji nor the sitar actually arrived. Perhaps they 'forgot'...