Darjeeling is one of India's most famous hill stations; it is, of course, renowned for its tea. Most of the hill stations I've visited – the Cameron Highlands, Kodaikanal, Dieng and so on – are situated in valleys, with a pleasant town centre surrounded by hills studded with beautiful residences. Not so Darjeeling; this hill station lives at an altitude of 2134m on a west-facing slope, which makes it easy to work out which direction you're facing, but it also makes exploring the town feel like a workout on a step machine.

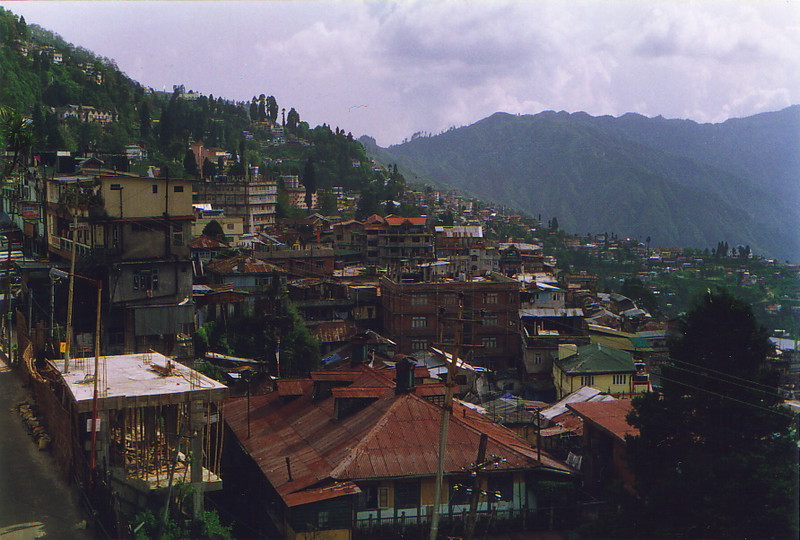

The town itself is fairly large. From above, Darjeeling looks like most Indian dwellings, with rusty tin roofs, ugly black water tanks and washing draped just about everywhere, but the slope manages to prevent the claustrophobic feeling that I normally associate with closely cropped and crowded places. Walk up the hill and you can look down on the whole town with views all the way down to the deep valley floor below, and if the weather is clear you can see the western Himalayas dominating the horizon, with Everest just visible as a deceptively diminutive peak among the closer mountains.

That's if the weather is clear, though. Like other hill stations, the summer temperatures in Darjeeling are simply divine compared to the sweat and toil of the plains below, but the price you pay as the monsoon approaches is a lot of cloud, a fair amount of rain and a total lack of views. My hotel room, complete with balcony and the familiar stain of wet mould in the corner, would have provided me with the perfect setting for sipping tea and talking politics, but in the end all it could manage was a view reminiscent of that from a 747 flying over wintry Europe. I'd expected this, and having spent weeks surrounded by the Himalayas I wasn't that disappointed not to be able to see the mountains, but it did make it harder to get motivated about exploring the area.

Occasional glimpses through the fog made it worthwhile, however, and I met up with a couple of very friendly Irish travellers, Chris and Martina, who proved excellent companions for exploring the hill station. The snow leopard sanctuary, which has the only breeding programme in southern Asia and the only one in the world that has had any kind of success, was well worth the hour's walk from town; the endangered snow leopard is a superbly beautiful creature, especially the cubs, and as they gambolled round their cages we talked to the man in charge of the programme, learning as much about Asian politics as we did about snow leopards.

The grandly named Darjeeling Rangeet Valley Passenger Ropeway is another interesting attraction, not so much because the cable car is anything fantastic (though the views over the rolling fields of tea bushes are decidedly photogenic) but because the thrill of putting your life in the hands of the first ever Indian cable car really gets the adrenalin flowing. Rattling our way down the hill and back up again in a car complete with smashed window and a door you couldn't open from the inside, we managed to complete the journey without serious incident (luckily the ropeway isn't steam-powered).

It is, however, a good way to get below the high cloud that smothers the town at this time of year, and at last we managed to get a glimpse of the Himalayas, albeit a long way away and not the group containing Everest. For the latter we had to be content with the Himalayan Mountaineering Institute Museum, a fascinating collection of stories and memorabilia from the various Everest expeditions; the late Tenzing Norgay, one of the first two1 to reach the top of Everest, lived in Darjeeling, and the museum he helped to set up is full of his equipment.

Then there's the botanical garden, a pleasant green park on the sloping valley sides just below the town, which is surprising not so much for its flora and ponds but for the peace and quiet which it affords; this makes hitting the high street a serious culture shock, with its myriad shops selling Tibetan goods and cramped market backstreets heaving with cobblers, tailors, pan shops and tea vendors. Darjeeling is a holiday spot in every way, and the number of Indian tourists milling around creating fascinating chaos shows just how popular such a set-up is.

But the most important thing to do in Darjeeling is to relax with a nice pot of tea and a good view or, failing the latter, a comfortable chair. Every day that we were in Darjeeling, Chris, Martina and I found our way to Glenary's, a reminder of the days of the Raj with its smart waiters, impeccable service, excellent food and an anachronistically high-ceilinged dining room that, in the winter, would be flickeringly lit by the roar of the fire at one end. But we didn't need a fire, we just needed tea; not surprisingly the tea in Darjeeling is excellent, and not just because it's served western-style. If you order chai in India, you'll get a grubby glass filled with an incredibly milky and teeth-crunchingly sweet concoction that is made by filtering violently boiling milk through the tea-maker's equivalent of an old sock filled with tea leaves, and after throwing it around a bit in a style faintly reminiscent of flashy bartenders – though that's where any similarity between an Indian chai stall owner and a waistcoat-clad cocktail expert ends, believe me – he'll present it to you with a bill for two rupees. It tastes wonderful and I'm a huge fan, but it's nothing like tea as westerners know it.

In Darjeeling, however, you get a pot of local tea, a tea strainer, a jug of hot milk, sugar in a bowl and time to enjoy yourself. Darjeeling tea is a mild-flavoured brew compared to fiery Lapsang Suchong or the slightly sickly spices of Earl Grey – experts probably use words like 'delicate' and 'subtle' when talking about Darjeeling tea – so it's a godsend that it's not treated with the usual Indian courtesy; the flavour would be totally crushed if it was served through a sock.

Tea isn't the only important part of Afternoon Tea, though; don't forget tiffin. Immortalised by Sid James in Carry On Up The Khyber – whose sessions behind locked doors with various big-bosomed beauties of the Raj were referred to as 'a bit of tiffin' – the Indian word 'tiffin' simply means a snack, and is yet another Indian word that has found its way into everyday English2. Tiffin in Darjeeling means cakes and lots of them, and between the three of us we managed to build up enough fatty residue to see us through the meanest of Indian illnesses. I shan't annoy you by mentioning the prices; suffice to say that a hoard of cakes and a couple of pots of tea came in well under £1, and that back in England I wouldn't visit an establishment like Glenary's without an expense account or a benefactor in tow. How the other half3 live...

Tea Terminology

The whole subject of Darjeeling tea deserves a separate section, if only because the sheer complexity of it makes PG Tips look positively plebeian. Ready for a whole new world? Then we'll begin.

Darjeeling tea isn't just one type of tea, it's a whole family of teas; talking about Darjeeling tea is a bit like saying someone speaks English, when they could be speaking Geordie, Australian, New Jersey, Inglish, Cockney and so on. And like accents, some teas have class and others just don't.

A look at the processing method used in the Happy Valley Tea Estate in Darjeeling shows how one bush can produce five different varieties. The picked leaves are placed in long trays to a depth of about 20cm where air is blown from underneath to drive out moisture in a two-stage process, with six hours of cold air and six hours of hot; this reduces the moisture content of the green leaves from 75 per cent to 35 per cent.

The leaves then pass into a rolling machine where they are rolled and crushed for 45 minutes to bring out the juices from the cells, after which a sifter machine separates out any leaves that are too big. Fermentation is next, where the leaves are left on cold metal shelves for two to three hours to ferment in their juices, turning the colour from green to brown; they are then passed through the drying machine, a long conveyor through a furnace set to 117°C where the moisture is reduced to about 2 per cent. Finally the leaves, now ready to brew up, are sorted into categories according to leaf size, with the smaller leaves being the best quality; at the Happy Valley the teas produced are, in order of quality with the best first, Orange Pekoe, Golden Flower, Golden Supremo, Supremo and Tea Bags.

But it's not just the drying and fermenting process that creates categories of tea, it's also the picking method used before the leaves are processed. Tea bushes are squat little affairs, and the leaves grow upwards in a manner reminiscent of bonsai yew trees; pruning is done off the top of the tree, and each branch produces three leaves: two mature outer leaves and a younger inner leaf. The best teas come from the tips of the mature leaves (as the younger leaf has less character), and so the picking method provides another part of the categorisation method.

The very finest Darjeeling tea is called Super Fine Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe, which is made from the top part of the two mature leaves. Next is Fine Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe, which is a coarse-plucking tea, meaning that all three leaves are plucked to make it. Then there's Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe, which has even coarser plucking (in other words, less care is taken). There is even a further distinction; the first two teas come from 'Chinese' plants with their small, thin leaves and better flavour, while the third comes from 'Assam' plants with their thicker leaves and stronger (but less delicate) flavour.

But what does all this jargon mean? This is where it gets confusing, but basically the 'Super Fine Tippy' part refers to the picking method, the 'Golden Flowery' bit refers to which grade comes out of the final sifting machine, the 'Orange' denotes the colour of the tea when it is put into boiling water (orange is good and means the tea is whisky-coloured as opposed to the cheaper teas which turn the water a rum colour), and 'Pekoe' means that the tea flavour comes straight from the leaves rather than from an added perfume.

So you've decided on the type of tea you'd like to buy, but things have only just started. Within each type of tea are four broad bands denoting the time of year the tea was picked, namely First Flush, Second Flush, Rain Flush and Autumn Flush. The differences between the various flushes are as marked as the differences between vintages of wine, because tea quality is very dependent on climate; and because bushes are plucked in blocks, with one block being picked every 15-20 days, the same bushes can produce very different teas. The tea-picking season runs from March to November, and the best teas are picked in March, the so-called First Flush; if tea is plucked after or during heavy rain, then the rain will have washed the flavour juices off the leaves and the tea will have less flavour, so the best flushes are during the dry spells (hence First and Autumn Flushes are good).

Then within the flush categories are more specific details, and the quality varies surprisingly. For example, First Flush Super Fine Tippy Golden Flowery Orange Pekoe from the fourth week in March retails at Rs600 per kilogram, but from the second week in March it costs Rs1100 per kilogram, nearly twice as much. It clearly pays to research the product before buying.

And in case you think you know it all before hitting the tea shop, there are countless other types of Darjeeling tea, from Bio-organic tea (when no pesticides or chemicals are used, which is true for all teas but in this case the estate has a certificate to prove it) to Green tea (which uses a different manufacturing process to the rest). That's without even delving into other regions and all their intricacies, such as Assam from India's northeast.

Of course the best way to buy tea is to ignore all the jargon and to go into the shop for a taste test of the product. Unfortunately your average tea shop doesn't have four hundred pots of hot tea for you to sample, so you have to check out the leaves themselves. Take a small pile of tea in your palm, close your fist and breathe through the tea to warm it up and moisturise it slightly. You then smell it with a deep breath and make your choice.

I have to confess that all the teas I smelled seemed very much the same, even though they looked quite different, with the expensive teas looking quite fine and the cheaper ones much more burned and scrappy-looking. The man in the tea shop confided that most of the locals can't tell the teas apart either; only those with lots of experience can. Still, it's all in the taste when you finally brew up.

But even then the tea experience isn't simple. Should you add milk? Should you take sugar? Well, it depends on the tea; stronger teas from the Assam plant (not to be confused with Assam tea, which is tea grown in Assam) are fine with a little milk ('Only a drop,' said the tea shop owner, 'because then they are getting the real tea taste') but the more delicate Chinese plant teas should be taken without milk. Oh, and make sure you store your tea in a metal tin, rather than plastic or glass.

So next time you settle down for a cuppa, think about what you're drinking. It's been through an awful lot, even before you start brewing up...

1 Hillary and Tenzing have always kept quiet about who actually reached the top first, which is interesting. If you ask a westerner who climbed Everest first, the answer will be 'Edmund Hillary'; ask someone from the Indian subcontinent and the emphasis will be on Tenzing Norgay. They're both right, because nobody knows who was first except for the two who made it, and they're not telling; there are no clues in the photos, either, as the flags flown on the summit were the Union Jack (for New Zealander Hillary), Indian (for Norgay) and Nepalese (as Everest is in Nepal).

2 There are lots of Indian words that have made it into English. Veranda, guru, pyjamas, sandals, ganja, dungarees, shampoo, khaki, jungle, loot, monsoon, hookah, curry... all these are Indian words that we commonly use today. There are more than you think.

3 One rich middle class Indian told me that if you have money, India is the best country in the world to live, and not just because it's cheap. With money you can live a lifestyle that's as good as anything you can get in the West, but your money can also buy you all the drugs you want, as much corruption as you like (by judicious use of baksheesh) and can even get you the perfect spouse and produce well-educated kids to ensure the family fortune stays as the family fortune. If money is no object in the West, you can still get anything, but if you're caught bribing, you can do time; in India, it's all part of the social fabric, so not only can you get away with it, you do.