Nepal freaked me out instantly, in much the same way the cool, silent night air does as you leave the rock concert, ears still ringing. Compared to the hustle and bustle of India, Nepal feels like a quiet backwater; the fact that I had to put my watch forward by exactly fifteen minutes at the border only emphasises the difference between India and the mountain kingdom to the north.

Even the long bus ride from the Indian border at Sunauli to the mountain town of Pokhara is easy, and the loud horns that are so ubiquitous in India are conspicuous by their absence. A fellow traveller told me that after India, anywhere would appear mundane, but I'm not sure that's such a bad thing; after all, sitting in a comfy chair in front of the fire and flicking channels is pretty mundane, but after a long day trekking through the fire and ice of the real world, it's a dream.

Indeed, trekking is my main goal in Nepal, and that's why I headed straight for Pokhara instead of Kathmandu. The Annapurna Conservation Area to the north of Pokhara, itself in the western half of Nepal, contains some of the most dramatic trekking on the planet, and I had my sights firmly fixed on the three-week Annapurna Circuit, a circular route that crosses a very high pass (Thorung La, 5416m above sea level), trundles down the deepest gorge in the world (the 5571m-deep Kali Gandaki Gorge), and provides mountain views to stifle breath that's already short in the high altitude of the Himalayas. After beaches, rainforests, deserts, volcanoes and glaciers, it's time for the big cheese.

The Himalayas are, of course, huge, but reading about them is considerably different from experiencing them first-hand. On a trek like this there are not only the usual walkers' concerns of blisters, twisted ankles, upset stomachs and sunburn, but also Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS), an ailment brought on by high altitude that is fatal if unchecked, and which still claims trekkers' lives today. On the surface, the Annapurna Circuit sounds like the biggest challenge of them all.

It isn't all challenge, though, and this is a major part of its appeal. Unlike most of the trekking I've done up to this point, you don't need to carry food because you stop in villages along the way, staying in the local hotels. This also means you don't need to carry a tent, cooker, fuel or any of the other gear associated with self-sufficient wilderness walking, which leaves the pack pleasantly light and the accommodation comfortable. On a three-week trek this is a godsend; the thought of a pack laden with 21 days of survival gear is enough to make most people's knees spring a leak in sympathy, mine included.

It also means that I have to reappraise my attitude towards long-distance walking. I've been on so many walks that require serious effort and long days to get anywhere – Taman Negara, Hollyford-Pyke and Gunung Rinjani to name but three – that I've developed a bit of an attitude problem. I like to go fast, to push myself, to get fit, to be first at the destination, and in Annapurna this isn't just a waste of the ambience of the village inns and the beauty of the mountain views, it's foolhardy. The best way to avoid AMS is to acclimatise slowly to the altitude, so zooming up the peaks is simply dumb. Altitude requires a different attitude, there's no doubt about it.

Annapurna Statistics

The Annapurna Circuit is a loop that's normally walked anti-clockwise; it circles round the east-west Annapurna mountain range, starting and ending at Pokhara to the south of the range. These mountains are huge; the tallest, Annapurna I, reaches 8091m (26545 ft), a height approaching that of Everest's 8848m (29028 ft). The track doesn't quite reach such dizzying heights, but the 202km (125 mile) walk has a fairly hefty high point at its northern tip: the Thorung La pass is 5416m (17769 ft) above sea level, just under two-thirds of Everest's altitude. The highest I'd ever been before tackling the Annapurna track was 3726m (12224 ft) on Lombok's Gunung Rinjani, but the Thorung La pass is nearly half as high again, and it feels like it.

The pass neatly slices the track into two halves: the section from Pokhara to Thorung Phedi, which takes you up to the eastern side of the pass; and the track from Muktinath back down to Pokhara on the western side of the pass, which is popularly known as the Jomsom Trek and is commonly walked by those unwilling to tackle the pass.

In 1993/4, 5898 walkers headed up the eastern side; in the first half of 1997, 18.1 per cent of those walkers were from the UK, 11.4 per cent from Germany, 11.3 per cent from the US and 9.7 per cent from France. Conversely, on the western side there were 15822 walkers in 1996/7, of which 13.7 per cent were from the UK, 12.7 per cent from Germany, 10.5 per cent from France and 9.2 per cent from the US. The pass sure puts people off, and because the western side is more luxurious than the east, hardly anyone just does the eastern trek, as shown by the fact that there are three times as many walkers on the Jomsom as on the Circuit.

And those walkers doing the whole Circuit will pass through 73 villages in 90 hours of walking, with 540 hotels to choose from with a total of 5218 beds. Annapurna means business.

Annapurna Trekking and AMS

'A lover without indiscretion is no lover at all' reads a poster in the tea shop a few days into the trail, and the total nonsense of the message seems quite in keeping with the contradictions you can see along the trail. Slashing a route through the deepest mountain valleys, the Annapurna Circuit passes through villages that used to be almost invisible, but which now sport signs in English, shops selling western luxuries, hotels with hot showers and even international telephone booths for those people who can't resist intruding on the outside world. The Annapurna Circuit isn't known as the Apple Pie Trail and the Coca-Cola Circuit for nothing.

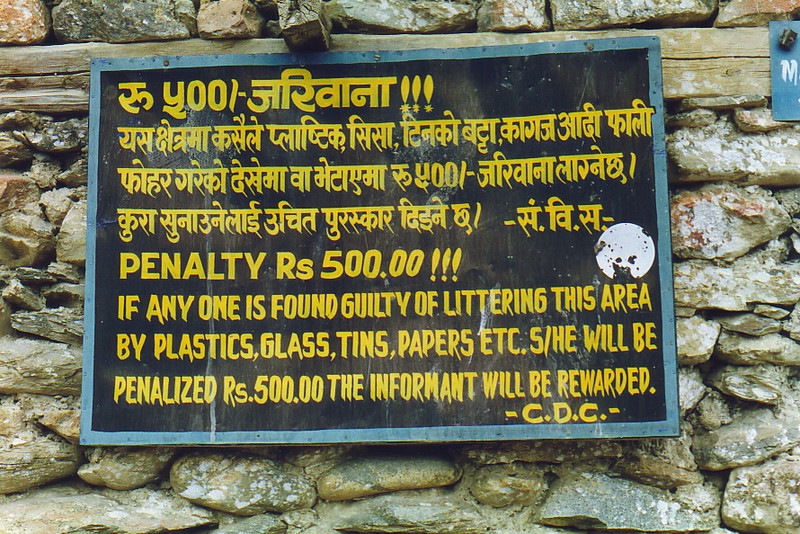

This type of trekking has its ups and downs in more than just the literal sense. The impact of tourism on this erstwhile netherworld is plain to see: piles of bottles lie cracking in the searing sun, candy wrappers litter a number of the paths and the local culture is hard to separate from the service industries of hotel and restaurant. On the plus side, though, income is higher, ecological awareness is increasing, and the litter problem is nothing compared to India or Indonesia, an impressive feat when you consider the sheer number of people involved.

The Circuit also has an image problem among hardcore trekkers, who see it as more of a long stroll than a serious challenge. Trekkers who are more at home in waist-deep swamps and leech-infested tropical rainforests call it the 'milk and honey trek' because of all the luxuries you encounter on the way – shops, real beds, bottled water and so on – and indeed Peter, with whom I trekked in Sulawesi, described the Circuit as more of a collection of day walks than a real trek. In a sense he's right because most of the days are fairly short in terms of time and distance, but I'm not sure I'd say that the Circuit is easy; I found the Annapurna Circuit a phenomenal challenge, though perhaps for different reasons than normal.

With such a walk one doesn't walk alone, even if one initially sets out on a solo trek. The groups I joined kept changing as various people went at different speeds or succumbed to the demands of the trek, but the main people were great company. There were Clare and Anne, sisters from Vancouver; Jakob from Denmark; Bob from Cleveland, a veteran 13-year traveller; Sheldon from Australia; and a whole spectrum of other characters to liven the mix. Sharing walks, something I've tended not to do in the past, is a good thing when your nightly stops are in hotels, and I soon realised that Annapurna is made to be shared.

Another thing to share is paranoia about AMS. If you could take a man from sea level and transport him straight to the top of Everest – which, incidentally, is impossible because helicopters don't have enough air at that height to operate – then he would sink into a coma after two minutes, and be dead after four. This is down to a combination of the lack of oxygen and the low atmospheric pressure at that height; on Thorung La, the highest point of the Circuit, the atmospheric pressure is half that of sea level, and the partial pressure of oxygen (i.e. the amount of oxygen in the air) is a third of that at sea level, as oxygen is heavier than nitrogen. The result is that without slow acclimatisation, people can die from AMS on the Annapurna Circuit, and they do, although not in high numbers (it's about one in 30,000 trekkers).

This sort of challenge provides plenty of food for thought for trekkers whiling away the hours in their hotel restaurants. In a display of group psychosis that is rarely seen outside village knitting circles, AMS is the subject of the moment. Every other question seems to be 'Do you have a headache? Are you on Diamox? How many acclimatisation walks have you done today?' It would be boring if there weren't so many conflicting opinions as to the truth behind AMS.

AMS is still a bit of a mystery, even though scientists know exactly why it happens and how to prevent it. The difficulty is that everyone seems to react differently to increased altitude; some might be able to go all the way from 300m to 5500m in a day without any symptoms, and some will die if they do the same. The guidelines are simple, though; when you get to 3000m you should only ascend 300m in each day, you should try to go on an acclimatisation walk to a higher point than your sleeping height, and at the sign of any symptoms you should stop ascending and, if they don't go away or get worse, you must go down. Descent is the only treatment, and the recommended drug, Diamox, is only an aid to quicker acclimatisation, and is not a cure.

It's made even trickier because the symptoms of AMS are a headache, reduced appetite, nausea, a loss of good humour, a congestive cough, and in serious AMS, ataxia (wobbly legs) and vomiting. These symptoms are fairly common on all long walks, with their exhausting days, uncomfortable beds and dubious food, so the paranoia runs rife, and with the temperatures well below freezing on the higher parts of the track, you have to wonder if your headache is from the icy blasts of wind freezing your ears off, or genuine AMS.

But still, what a beautiful place to walk...